Esters, Volatile Compounds, and Congeners - What's the Difference?

As more high-end brands target the enthusiast crowd with expensive bottlings, their customers naturally want to know more than the typical label provides. One helpful detail some brands provide is the “ester level.” However, other measurements are sometimes provided alongside or instead of an ester level.

To state things very clearly up front, esters, volatile compounds, and congeners are different but related concepts. Without some technical background, it’s easy to misunderstand what each measurement conveys and come to the wrong conclusion. In what follows, I’ll provide some necessary background and then wrap things up with real-world examples and guidance.

Organic Compound Introduction

A 40% ABV (80 proof) rum contains 40% ethanol, around 59 percent water, and one percent or less of other organic compounds. For a typical bottle, these other compounds contribute around 7 ml or less (about one-quarter of an ounce.)

Water contributes no flavor to a rum, and ethanol contributes very little. Thus, nearly all of a rum’s flavor comes from a very small portion of its organic compounds. Call them flavor compounds if it makes things easier to understand.

Everything we smell—be it a strawberry, burning plastic, rotting eggs, wet dog, or freshly cut grass— results from organic compounds in the air reaching our nasal receptors. Our olfactory system (nose and tongue) can detect these compounds in exceedingly small concentrations, e.g., one part per billion.

A rum’s particular mix of organic compounds forms at different points during its creation —some are created during fermentation, while others are introduced during aging. The distillation process primarily filters and concentrates rather than creating many new compounds.

A rum’s organic compounds can be placed into several categories based on their chemical properties. To keep things simple, I will discuss just a few categories, as the full set is beyond our scope here. They are:

Fatty acids

Alcohols (methanol and higher alcohols)

Esters

Phenols

Lactones

Let’s look briefly at each.

Fatty Acids

The most common acid in our everyday life is acetic acid, found in vinegar and other foods. Chemically, acetic acid has relatively few atoms, making it one of the simplest acid molecules. Butyric acid is slightly more complex, i.e., more atoms, and described as smelling like vomit. Even more complex acid molecules, including lauric, palmitic, and oleic acids, are found in “fatty” foods and soaps. In bottled spirits stored at low temperatures, the more complex forms of fatty acids may clump together and become visible as a cloudy haze. (See also: chill filtration.)

Alcohols

The most common alcohols we’re readily familiar with are ethanol, methanol, and isopropyl. The latter is the core ingredient in rubbing alcohol. Ethanol is the primary alcohol present in distilled spirits, although methanol and other alcohols are produced by yeast during fermentation. The molecularly more complex (heavier) alcohols are known as higher alcohols or fusel oils and may play an important role in the aroma of some rums. Distillation removes most or all the alcohols we shouldn’t consume, e.g., methanol.

Esters

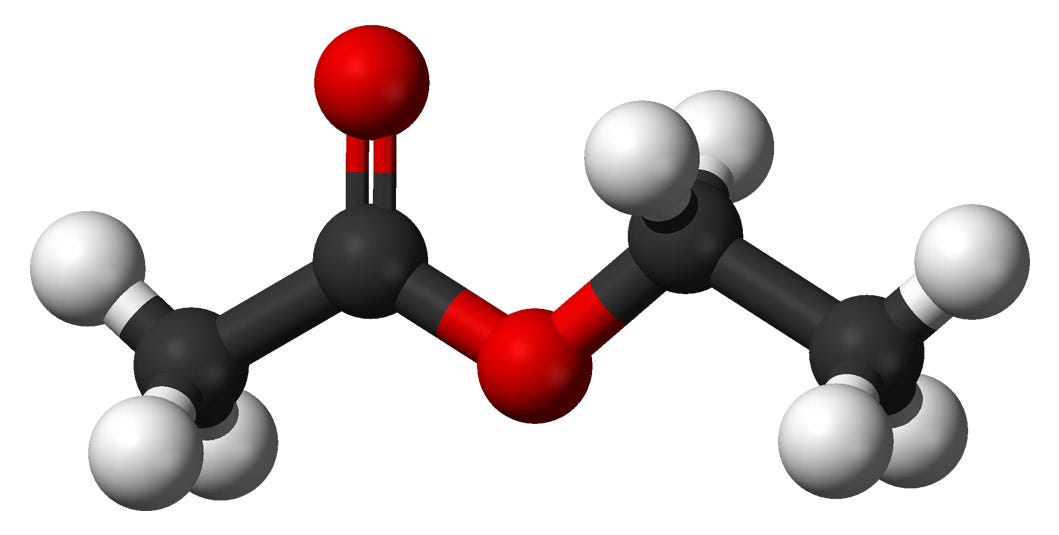

When it comes to rum, esters get special attention from enthusiasts. Esters provide sweet fruity aromas like apple, banana, and pineapple, as well as scents like coconut, honey, and chocolate. There are hundreds of different ester types, each formed from a unique combination of alcohol and acid molecules.

In the simplest terms, one alcohol molecule plus one acid molecule results in one ester molecule.

For example, ethyl acetate is an ethanol and acetic acid molecule bound together and by far the most common ester in rum. Likewise, ethyl butyrate smells of pineapple and is a combination of ethanol and butyric acid molecules. Isoamyl acetate is described as “fake banana” or “circus peanut” and results from isoamyl alcohol and acetic acid molecules binding together.

The simpler esters generally have fruity notes, while more complex esters bring coconut, honey, and flowers to mind. During aging, esters may break apart and/or reform into more complex esters and increase in quantity.

Phenols and Lactones

Phenols and lactones are both categories of organic compounds and provide aromas and flavors like wood, smoke, creosote, bacon, clove, and nuts. In general, these compounds appear during cask aging rather than during fermentation.

A Brief Note on Congeners

Before we move on to how we measure flavor, let’s address the term congener, as it is frequently misunderstood/misused. To paraphrase Wikipedia: In the spirits industry, congeners are substances other than ethanol produced during fermentation. Any organic compounds introduced during the aging process are not congeners.

Measuring Flavor

With so many different organic compounds swimming around in our rum, we naturally want to measure them, i.e., “What’s in there, and how much of it?”

There are many highly advanced techniques to determine what’s present in a rum, but the most common technique is gas chromatography. These days a good gas chromatograph costs around USD 40,000 and requires substantial expertise to operate. Most commercial rum distilleries have at least one gas chromatograph (“GC”) in their laboratory.

In the scientific analysis of spirits, the quantity of organic compounds is usually given in grams per 100 liters of pure alcohol. (That is, 100 liters of spirit if all the water wasn’t counted.) The common abbreviations for this unit include gr/hlpa and gr/hlAA. (hl means hectoliters; pa means pure alcohol; aa means absolute alcohol.)

A typical ester measurement for a rum is 70 gr/hlAA. What does that mean?

Imagine you had a big tank of this rum. You snap your fingers, making all the water vanish so that only ethanol and the other organic compounds remain. If you then took 100 liters and analyzed it, there would be 70 grams of esters. Or in Imperial units, about 2.5 ounces of esters in every 26.5 gallons of liquid

For over a century, Jamaican rum producers and blenders have used ester levels to define different tiers of flavor/quality known as marks, aka marques. However, as we learned earlier, esters are just one part of the flavor story. A simple analogy helps to illustrate this.

Imagine you are asked to assess the overall color intensity of a painting using a scale from 1 to 100. Using only esters to assess a rum’s flavor intensity is like estimating the painting’s color intensity considering only the blue color. If the painting were vibrantly blue, you’d give a value close to 100. But if green or red were the pre-eminent colors, your measurement would be close to zero.

Esters are just one dimension in a multi-dimensional flavor equation.

A Better Way to Measure - Volatile Compounds

With today’s advanced tools, we can learn much more about a rum’s content than just the ester level. Several decades ago, the European Union defined a set of organic compounds related to spirit flavors and aromas:

Volatile acids

Aldehydes

A subset of the higher alcohols

Ethyl Acetate (the most common ester)

The quantity of each compound can be added together to create a single value known as volatile compounds or volatile substances, and esters are just part of that value. The unit of measurement remains the same: gr/hlAA.

A brief aside: volatile in this context means compounds that can readily pass through the distillation process. In contrast, non-volatile compounds are so heavy that they can’t pass through the distillation process. Sugar is one notable non-volatile compound, which is why we know any sugar in a rum was added after distillation.

Volatile substance levels find use in several geographical indications, including those of the French overseas territories. Both Martinique’s AOC and Guadeloupe’s PGI require that unaged rums have at least 225 gr/hlAA, and aged spirits must have at least 325 gr/hlAA.

Learning From the Data

Let’s now look at the measurements for a real-world rum to illustrate an important point from earlier. I’ll provide the raw data and commentary without revealing what the rum is until afterward.

Rum ‘X’ has the following measurement regarding esters:

Ethyl Acetate: 60 gr/hlAA

Total Esters: 63 gr/hlAA

63 gr/hlAA is several times higher than you’d expect to find in a light Cuban or Puerto Rican rum. However, 63 gr/hlAA is pretty low within the realm of Jamaican rum. It doesn’t even meet the minimum ester level required to be a Common Clean rum. Common Clean is the lightest of Jamaica’s old-school mark system. (See also: Plummer, Wedderburn, and Continental.)

Based on Rum ‘X’s ester level, you might assume it’s mild to moderately flavored, i.e., nothing too intense.

However, other measurements reveal a very different story:

Higher alcohols: 374 gr/hlAA

Volatile Substances: 535 gr/hlAA.

These values are in the same range as certain Jamaican rums often described as quite flavorful or “funky.”

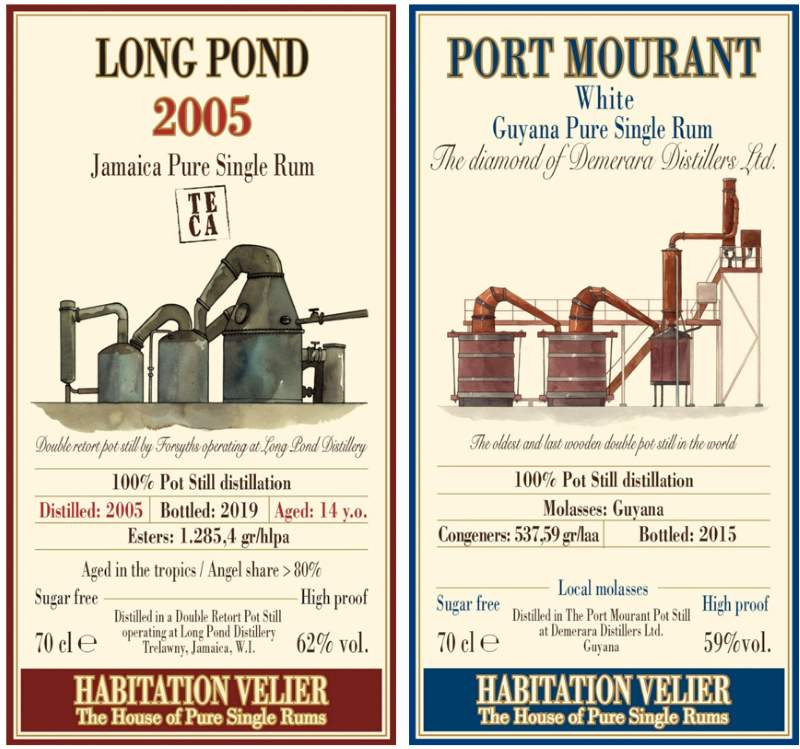

The big reveal: Rum ‘X’ is aged Port Mourant rum from Demerara Distillers. It’s no shrinking violet when it comes to flavor. I find it very easy to pick it out in a blend, and it was a core component of Royal Navy rum.

The moral of the story? Rum flavor is much more than just esters.

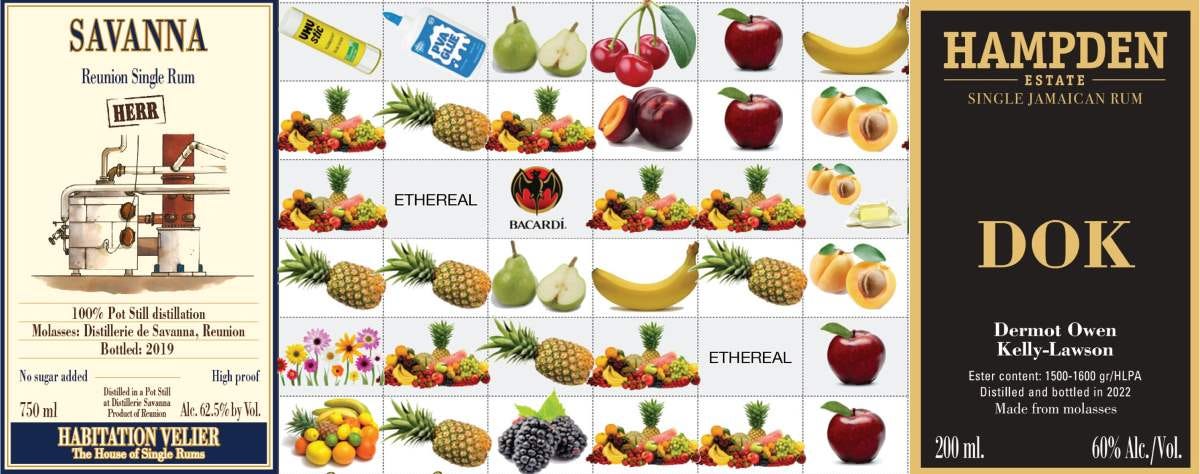

Real World Label Examples

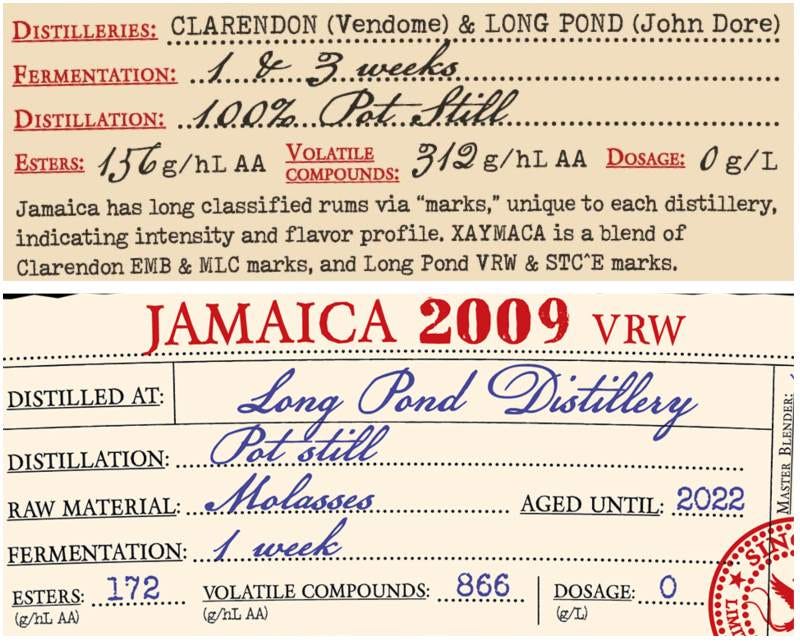

Among the major rum brands, Velier and its partner brands like Hampden, as well have Plantation, have been the most consistent about sharing technical details for their various releases.

A survey of recent Velier labels shows that some provide esters, others provide congeners, and some don’t provide either. I confirmed with a Velier representative that congeners on their labels refers to volatile substances.

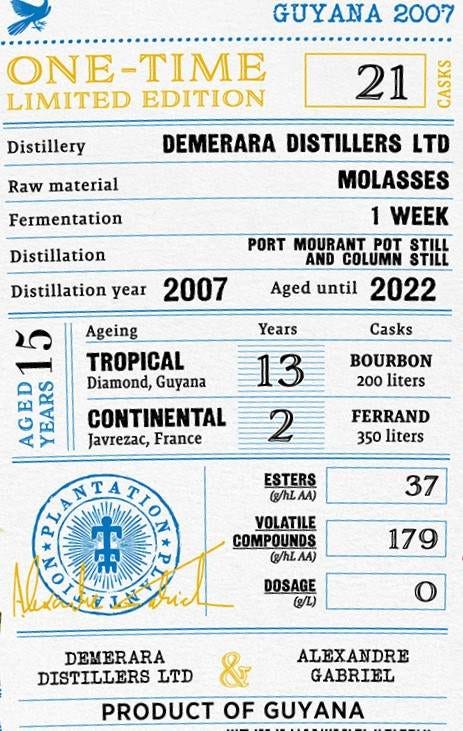

Plantation also doesn’t provide these technical details on every label. However, in recent years, all their annual single casks expressions have included esters and volatile substances.

Look at the above two labels, both Jamaican rums. The top label is Xaymaca, part of their regular portfolio. The other is a “single cask” 2009 VRW mark from Long Pond. The esters levels are reasonably close (156 vs. 172 gr/hlAA,) but the VRW’s volatile substances are nearly three times higher than the Xaymaca. The key takeaway (again): ester levels aren’t the sole (or best) metric to judge a rum.

In Conclusion

With rum brands starting to disclose more technical information, it’s important to understand the information they provide. You can’t just take a measurement from one brand and compare it to another brand’s measurement; you must make sure it’s an apples-to-apples comparison. Esters, volatile substances, and congeners aren’t the same thing.

Two rums with similar ester or volatile substances measurements may taste very different. To use an analogy, these measurements only tell you how loud the music is, not what style is playing. Furthermore, rum undergoing aging can experience significant changes —upwards and downwards — in compound levels. Comparing unaged distillates to their long-aged version can be very confusing. Ester levels increasing with age is but one example.

Finally, for those wanting to learn more, the introduction to organic compounds at the beginning of this story was adapted from Modern Caribbean Rum chapter 10 (“Rum Flavor Science.”) The full chapter goes an order of magnitude deeper into these topics.

Matt, I believe this is your best article yet. Quite informative of an extremely important subject, and just sophisticated enough to be educational yet light enough to be entertaining. Many thanks - Dave

Matt, I work in 2 Independent “bottle shops” (alcohol & no/Lo alcohol retail outlets) on the Sunshine Coast in Qld, Australia. It’s a semi-retirement, rather low paying casual “passion” job that I love. I’m constantly researching numerous information sources to increase my knowledge on all things “booze & non-booze” to enable me to sell with authenticity & trustworthiness. Your posts and insights on all things Rum are absolutely and categorically the most authoritative, insightful and enjoyable reading I’ve come across in the booze media globally. Please keep up the good work & I’ll definitely be buying your book in the New Year. Cheers & thanks greatly for your passion and knowledge sharing 👏