Is it Safe to Drink Old Rum?

Every so often on social media, I see a question along the lines of, “I found an old bottle of rum in my grandparents’ basement. Is it safe to drink?”

It’s entirely reasonable to ask. After all, if you found a can of tuna or a jar of spaghetti sauce from the 1950s, you’d rightfully be concerned. There’s a good chance opening it up and consuming it will turn into an unpleasant, if not dangerous, experience. But when it comes to bottled alcoholic liquids, the answer is, “Usually, but with some important criteria.”

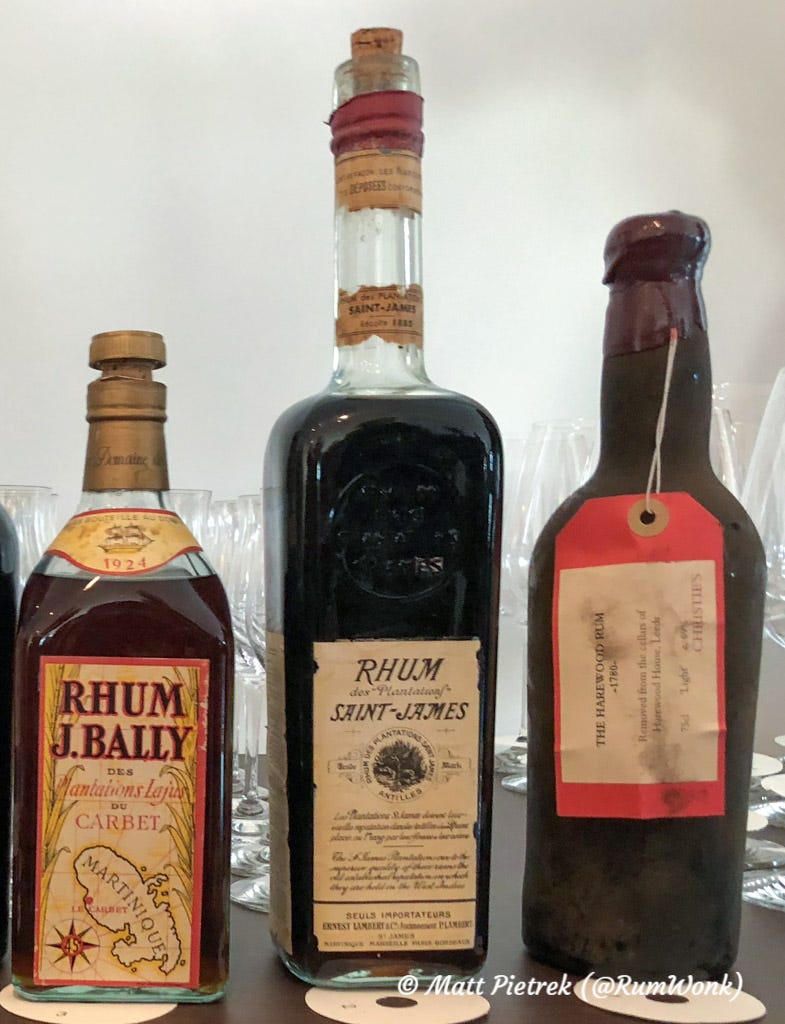

Over my years as a rum geek, I’ve been fortunate to taste several rums bottled over a hundred years prior. Among them, a Jamaican London Dock rum from the 1890s, shared with me by noted rum collector Stephen Remsberg. Others include a Rhum Saint James botted in 1885, and a 1924 Bally from Martinique. But the crown jewel of these experiences was the now-legendary Harewood House Barbados rum bottled circa 1780.

Preserving the Past – Strength Matters

Alcoholic beverages have an advantage over other consumables in that the ethanol within acts as a natural preservative to inhibit microbial contamination (“mold”) from taking hold. However, the degree of preservation roughly correlates with the liquid’s alcoholic strength.

Wine, vermouth, or something similar at 10-15% ABV has higher odds of going off than a distilled spirit at a significantly higher ABV. There aren’t any hard and fast rules here, but a properly sealed bottle of any distilled spirit is usually a safe bet to drink if bottled at 40% or higher. The well-known vintage bottle collector Eric Witz notes that liqueurs with high sugar content have an additional advantage in staying fresh, as sugar is also a preservative at sufficiently high levels.

With that background covered, here are a few common-sense steps to take before cracking open a bottle of dusty booze.

Examine the Evidence

The simplest way to ascertain if a bottle was properly sealed is to look at it. In particular:

Does it look like it’s been previously opened?

The fill level of the liquid.

For the first item, many old liquor bottles have paper tax strips affixed across the top. If there’s evidence of a missing tax strip, or if it is loose or broken, it suggests—but doesn’t prove, that the bottle was previously open.

As for the fill level, if the liquid level in the bottle is significantly lower than you’d expect, there’s a good chance that the cork, cap, or other closure hasn’t effectively kept the liquid in and the outside air out. The fill level is one metric vintage spirit collectors use to assess if they’re willing to take a chance on buying an old bottle.

However, even if a bottle passes the above tests, it doesn’t guarantee the contents taste like they did when first bottled.

Popping the Cork

Before opening your find, it’s worth pondering whether this bottle could interest a collector who might pay handsomely for it. There are several online resources where you can get a sense of whether your bottle is a sought-after-rarity or just another old bottle of 1977 Bacardi. (Many will jokingly say, “It’s not safe to drink. Send it to me, and I’ll dispose of it for you.”)

Assuming you don’t sell your found treasure, carefully remove the bottle’s cork or other enclosure. If it’s a cork, examine it closely and smell it. If it smells rancid or “off,” there’s a good chance the contents aren’t what they once were. Maybe the bottle was stored on a hot radiator or a sunny windowsill for many years, forever diminishing the liquid within.

If the cork crumbles, not all is lost! A crumbled cork doesn’t necessarily mean the bottle’s contents have gone bad. Pour the bottle’s contents through a very fine metal strainer; metal coffee filters work well.

Finally, pour a small sample and take a very small sip. Be prepared to spit it out if your brain says, “Don’t drink this.” A bad-tasting bottle is rare but not unheard of. If it tastes reasonably like you’d expect that type of rum to taste like, it’s probably OK to invite a friend or three and enjoy!

Stacking the Deck

As a final observation, there are a few famous and very vintage rums that command nosebleed-level price tags. In some instances, they have a little-known advantage that ensures the liquid in the bottle is up to snuff. Their leg up is that the rum’s original container has already been opened up, the rum evaluated, and any bad rum removed from consideration.

When the Harewood House bottles were first discovered in 2011, there were 59 bottles in the lot, but only 23 were auctioned off. The 2013 auction notes from Christie’s notes of those bottles: “…over half were rejected for sale because of failed corks or very low levels resulting in only 23 bottles being considered suitable for recorking and sale at Christie’s.”

Another well-known example is Black Tot Last Consignment, which is actual Royal Navy rum originally stored in one-gallon stone flagons since the 1950s and 1960s. In the very early 2000s, Sukhinder Singh, The Whisky Exchange’s co-founder, purchased several thousand flagons from a variety of sources. Circa 2009, a subset of the flagons was opened, and the rum was evaluated. Rum dubbed not up to snuff was removed, and a blend was created from the remaining “good” flagons. For a rum costing around USD 1,000 a bottle, you certainly wouldn’t want to risk including rum from bum flagons in the blend.

To wrap all this up, if you have an old bottle of rum — or any distilled spirit, you can start with the assumption that it’s likely OK to drink, again, assuming it has a high enough alcoholic strength. If it then passes the commonsense evaluation steps described above, you’re probably OK to enjoy your found treasure.

Last but not least, a shout-out to Eric Witz who reviewed this post for accuracy and supplied several of the photos.

Fantastic piece, Matt! Many of us are intrigued by the history and opportunity associated with these old and rare bottles.

Recently found a bottle of rum that Mom & Dad rip bought in 77 while on a cruise, I had retired from drinking but curiosity got me, it had been opened but sealed tightly, so I tipped the bottle , OMG HEAVEN IN THE BOTTLE! Truly no burn, aftertaste or chaser needed just true pleasure. I wish I had enough to share with everyone who would like a taste. I really do but sorry . Now about the bottle of over 100yr old Sherry I found with it , it was 50yrs old when they bought it for there 50th wedding anniversary, they missed placed it ,April 13 2025 would have been there 73 anniversary, I may open it then or maybe not, I've never had Sherry (the drink that is) any thoughts or should I send it to you for disposal. I was 13 when they got them now 62. BEST PARENTS EVER we went to Ron Rica... rum factory in the Dominican Republic I remember them filling my water cup with rum instead of the tiny shot cups they had, I was hooked, the rum he bought was from Puerto Rico, Ron del Barrilito brand , he bought several because it was duty (hehe duty still brings a smile when I hear it remember I was young then)free .Thank you for your time and enjoy every drink asif was your last one . Rum buddy 4 life ,best wishes and health to All.