Liqueur Rum? What the Heck?

Social media posts featuring photos of vintage rum bottles are rum aficionado catnip. And if the phrase “liqueur rum” appears on the label of the highlighted rum, someone inevitably comments:

“Liqueur rum? What’s that? Was it sweetened?”

While the short answer is “no” or “not necessarily,” the background of the phrase is worth understanding.

Today, we associate liqueur with flavored and sweetened alcoholic beverages like Chartreuse, Cointreau, and Cherry Heering. Outside the UK, “cordial” is a related term often used interchangeably with “liqueur.”

However, if we go back a few decades in our time machine, seeing “liqueur” on a label didn’t necessarily mean it was flavored and sweetened. It became fashionable to use “liqueur” as an adjective modifying the spirit type, e.g., “liqueur brandy” or “liqueur whisky.” When “liqueur” preceded the spirit type, it suggested a particularly refined spirit, perhaps best enjoyed in a crystal snifter after dinner. Marketing copy for these liqueur spirits often noted a lengthy aging of 20 years or longer.

Whether “liqueur” appeared before or after the spirit type was significant. For instance, “liqueur whisky” meant a long-aged, luxurious whisky, while “whisky liqueur” meant a sweetened, flavored beverage with whisky as the alcoholic base. Drambuie is a good example of a whisky liqueur.

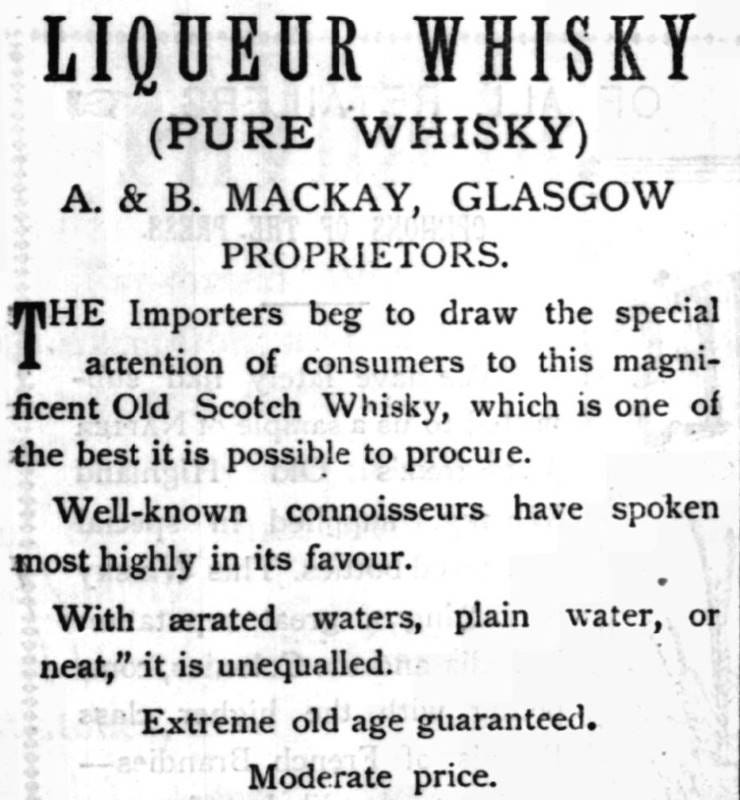

The golden age of liqueur spirits started in the 1880s as ads for liqueur whisky started appearing in British newspapers. One example is an advertisement for A. & B. Mackay of Glasgow which notes:

“PURE WHISKY … magnificent Old Scotch Whisky, which is one of the best it is possible to procure…. Extreme old age guaranteed.”

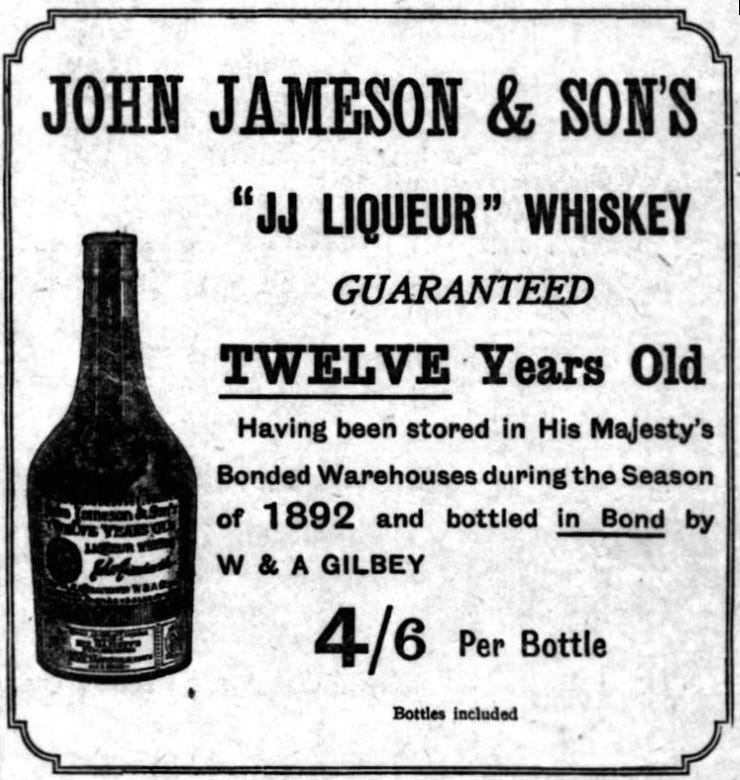

Another liqueur whisky maker of the era was John Jameson & Sons, the forerunner of today’s Jameson Irish Whiskey.

Given Britain’s voracious appetite for rum, it is unsurprising that liqueur rums like Pritchard’s Vatted were also available:

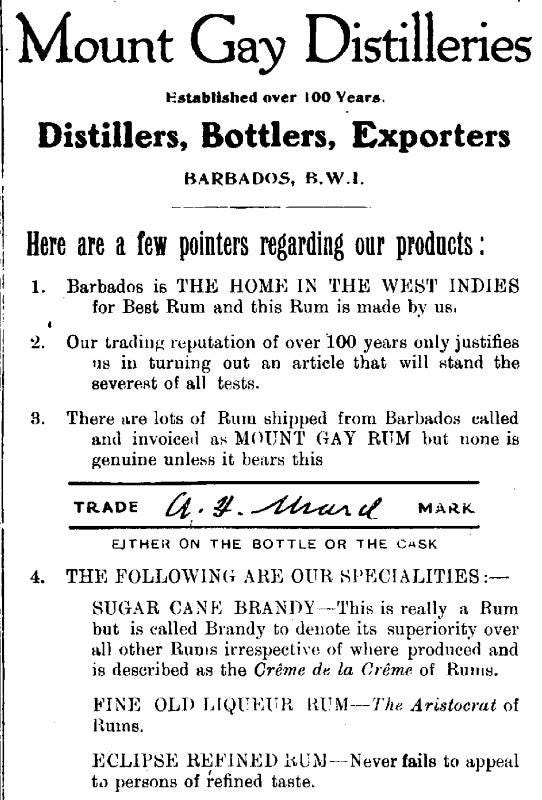

Eventually, Caribbean rum brands started using the liqueur rum terminology. In 1927, Barbados’ Mount Gay called its Fine Old Liqueur Rum “The Aristocrat of Rums.”

Likewise, Booker’s from British Guyana had a Demerara liqueur rum as early as 1937:

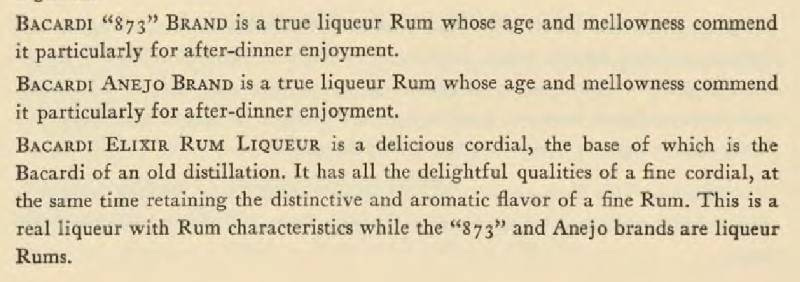

Circa 1940, Bacardi had two liqueur rums, “873” and “Anejo,” as well as a rum liqueur dubbed “Elixir.” The Elixir’s description notes the difference: “… a real liqueur with Rum characteristics while the “873” and “Anejo” brands are liqueur Rums.”

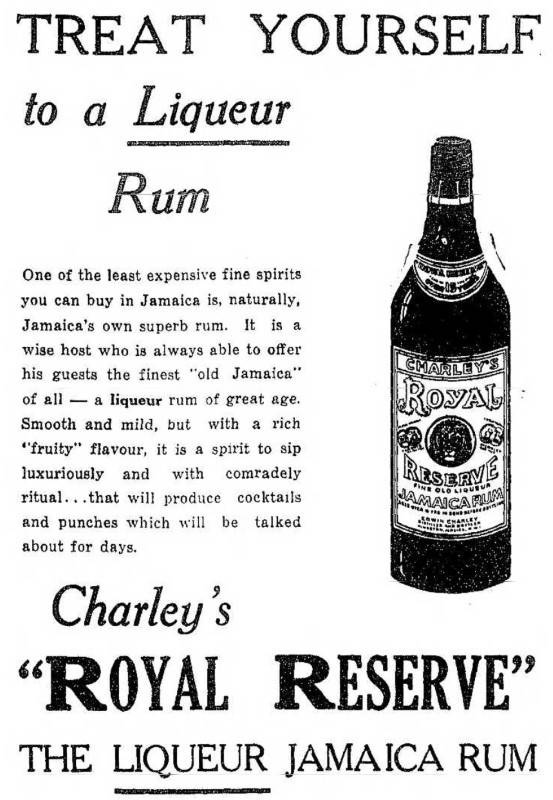

However, it was the Jamaican brands of the era that most embraced the use of liqueur rum to indicate a highest quality spirit. All the major brands had at least one liqueur rum, including Charley’s.

In the 1930s, Myers’ marketed two liqueur rums: “Mona,” distilled in 1906 and aged for ~30 years, and “V.V.O.,” distilled in 1895. Oh, to taste even a drop of either!

Coruba, in a World War II-era ad, noted “With Brandy Unobtainable Jamaica’s Selected Reserve adequately takes its place as an After Dinner liqueur.”

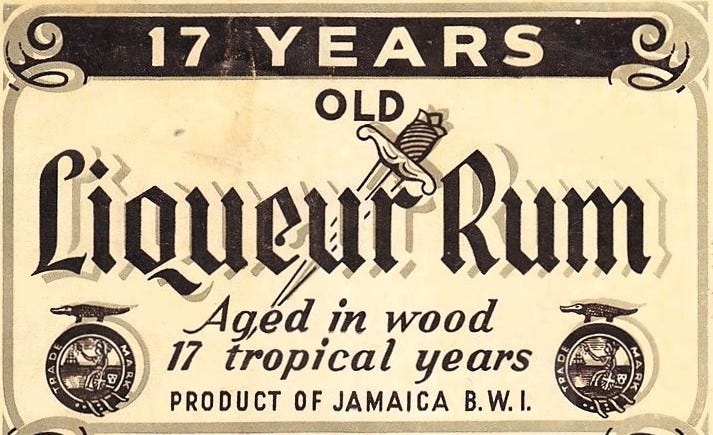

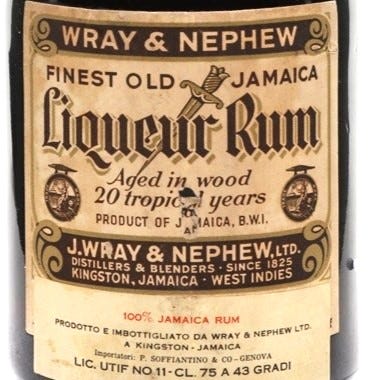

While the rums noted above are mostly unknown or forgotten, one liqueur rum achieved worldwide fame among rum geeks decades after its production and availability ceased. In 1944, Trader Vic pulled a bottle of Wray & Nephew 17-year rum from his bar shelf and created the canonical tiki cocktail, the Mai Tai. I’ve written quite a bit about Wray & Nephew 17, notably here and here, so I won’t dwell on it further. However, it is worth noting that Wray & Nephew also made 15- and 20-year liqueur rums with nearly identical labels to the 17-year.

The golden age of liqueur rums ended around 1960, although why the term fell out of favor is less certain. One theory is that a new generation of post-war drinkers associated liqueur with the stodgy imbibing habits of their parents.

Editorial notes: if you enjoy learning about vintage rums like the above, consider joining the Rum History group on Facebook. Also, a hat tip to Eric Witz for supplying the images of the Wray & Nephew labels pictured above.

Thanks so much for bringing this bit of history to light . =)