What Was London Dock Rum?

Chapter Excerpt from The Rum Never Sets

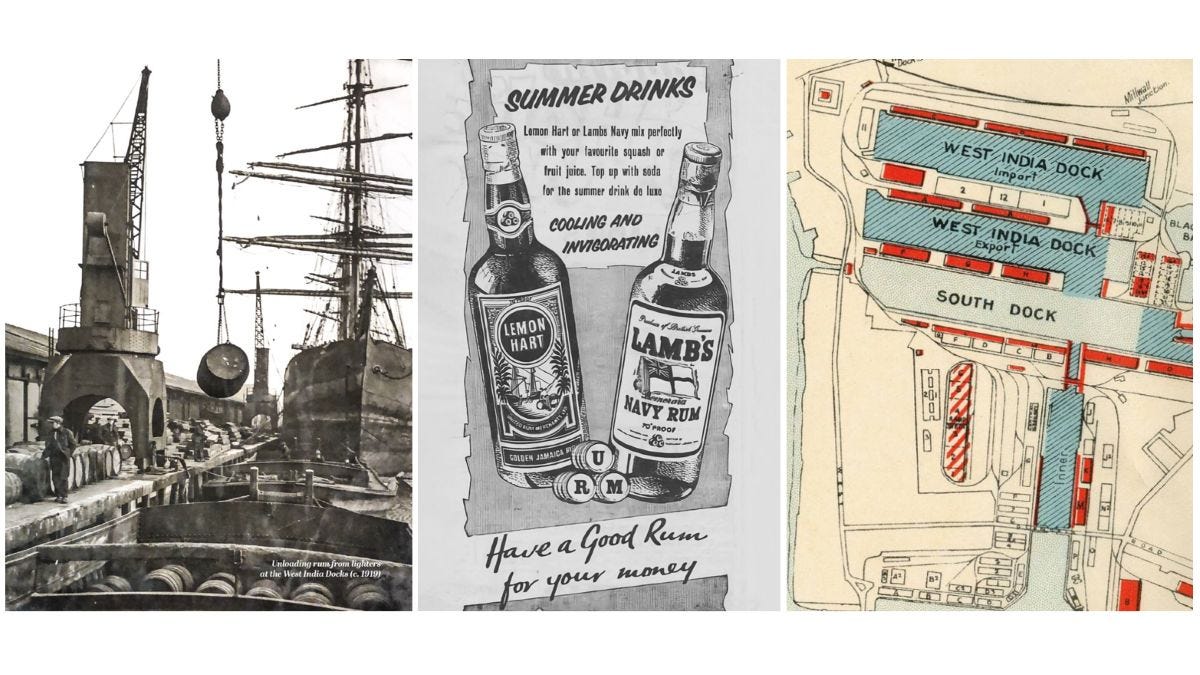

Today I’m sharing the first of several forthcoming chapter excerpts from my latest book, The Rum Never Sets: 300 Years of Royal Navy and London Dock Rum, co-written with Alexandre Gabriel. While much of the attention given to this book focuses on the Royal Navy’s rum, the book also dives deep into the London Dock rum and the West India Docks. Essentially, they were the consumer side of the British rum trade in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Without the infrastructure of the West India Docks and similar docks in other British ports, the Royal Navy wouldn’t have had easy access to the millions of gallons of rum it purchased and blended each year.

Preface

Before we get to the chapter excerpt, here is some important background context and terminology introduced in the prior chapter.

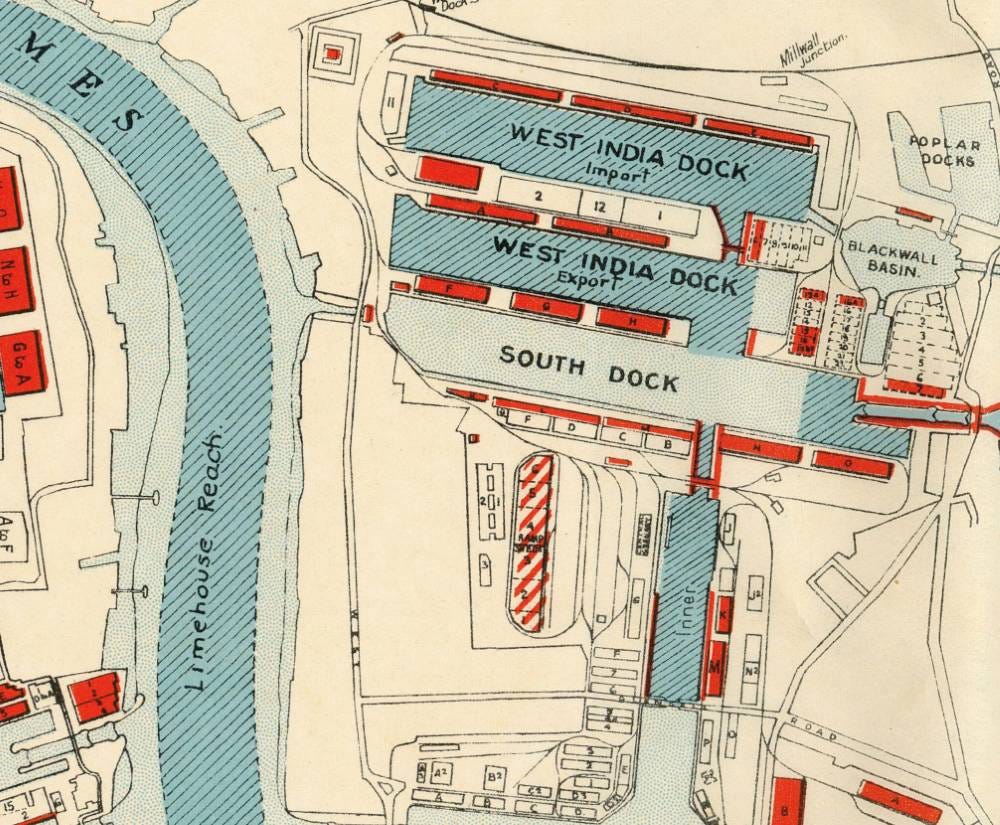

The West India Docks were a massive, man-made dock system carved out of the land in East London known as the Isle of Dogs. Today, we know the area as Canary Wharf. At the time of its construction (1800-1802), it was among the largest civil engineering projects in the world. Boats arriving from the West Indies would travel up the Thames and then enter the (mostly) land-locked dock system.

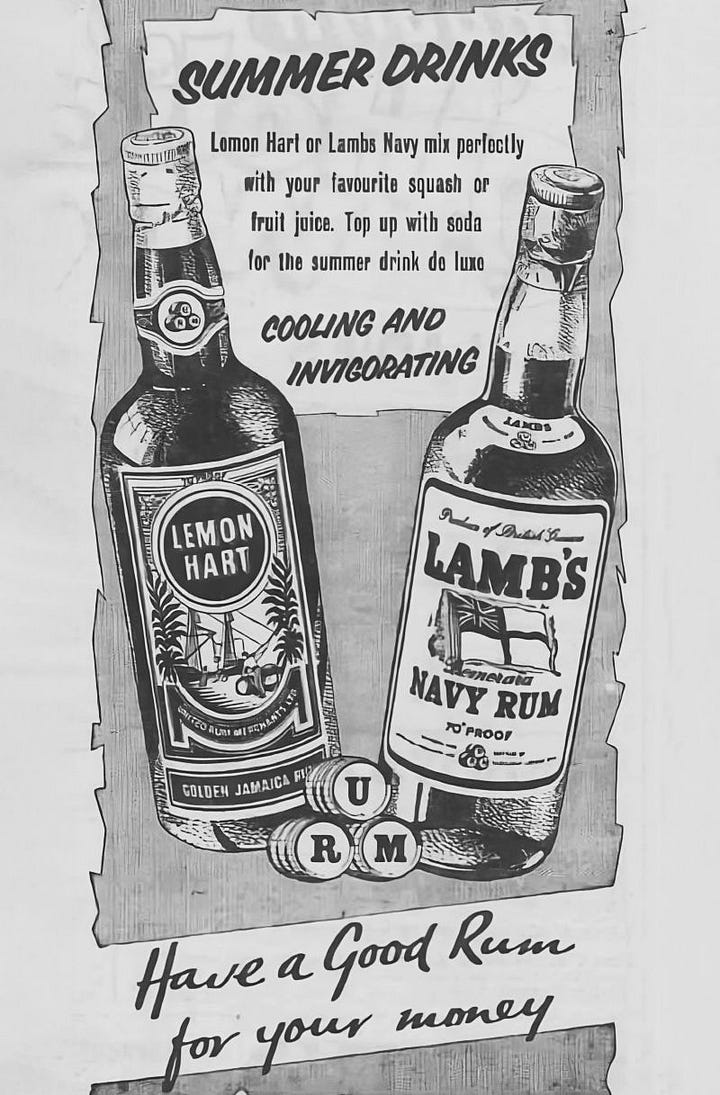

Rum Quay was a collection of buildings within the West India Docks devoted to storing and aging massive quantities of colonial rum in bond. Rum trading firms like Lemon Hart and Alfred Lamb imported and sold vast quantities of rum to the public, and these rums became known as London Dock rum. The same traders also sold to the Royal Navy, but that’s a story told elsewhere in The Rum Never Sets.

The heyday of London Dock Rum as a commonly used designation was roughly from the 1890s to the 1940s. A 1939 newspaper article provided a succinct definition of the style:

“London Dock” rums are distilled in Jamaica or Demerara, then barreled and sent to the London docks, where they are stored in the warehouses situated on the docks until properly aged. Eventually, they are bottled and shipped all over the world. This is where the name “London Dock” rum is derived— although the rum itself originates and is shipped in bulk from the West Indies.

In short, London Dock rum was “continentally aged” in today’s lingo. With this baseline definition in mind, let’s now dive much deeper into their history via the chapter excerpt below.

Chapter Excerpt - What Was London Dock Rum?

The story of every rum contains many chapters. From source materials, fermentation methods, and distilling to aging and blending, numerous choices impact the flavor. To better understand London Dock rum as a specific style of rum, it’s useful to first understand which types of rum came to Britain during the years in question.

RUM SOURCES

Production and trade volume records spanning more than two centuries show Britain had a strong preference for rums from its colonies. Longstanding business relationships, as well as British ownership of many plantations, certainly contributed to that preference; rums from French and Spanish colonies like Martinique and Cuba simply weren’t imported at high volume. However, Britain had numerous global outposts, so many colonies besides Jamaica and Demerara found representation in Rum Quay.

Each British sugar and rum colony had its own unique story to tell regarding its rum production and where it was consumed. Some peaked in production early and then declined, as was the case for Barbados, while others rose to prominence late in the game. Some were highly sought after and retained in London for home consumption. Others were not as valued and were exported from London to other markets.

While Jamaica, British Guiana (Demerara), Barbados, and Trinidad are known today as the major British rum colonies in the Caribbean, over the past three centuries there were many more. Some, like Suriname, are typically associated with a different European power; Suriname was briefly under British control before returning to Dutch control. Nonetheless, rum from Suriname found its way to London for a brief period.

Some colonies were combined to form new entities. The islands of Trinidad and Tobago are now a sovereign country, but in the 1800s they were treated as separate colonies. A reasonably complete list of rum-producing British colonies and other territories whose casks arrived in Britain and likely found their way to Rum Quay includes:

To get a sense of which types of rum came into Rum Quay, what follows is a brief synopsis of key British rum-producing colonies between 1800 and 1950. For a bit of perspective, one million gallons of rum per year meant the colony was a top-tier producer. At their peak, Jamaica and Demerara (now Guyana) produced more than four million gallons per year.

Barbados: Caribbean rum is thought to have been first made in Barbados circa 1640; a 1650 document directly references it. By the late 1600s the island was the largest rum producer in the Caribbean. Starting in the 1700s, Barbados rum production moderated, falling well below the level seen in Jamaica and British Guiana. In contrast to Jamaica, which sent most of its rum to Britain, Barbados rum exports went primarily to North America. George Washington, the first president of the new United States, was fond of Barbados rum and insisted on serving it at his inauguration.

Berbice: From 1830 forward, Berbice regularly exported more than 200,000 gallons per year. In 1831 it merged with Essequibo and Demerara to form British Guiana. However, rum production in Berbice continued to be tracked separately for a few years afterward.

Demerara/British Guiana: Although Demerara was not a British colony until 1815, it rapidly became one of the Crown’s largest rum suppliers. In 1831, British Guiana was formed from the Demerara, Berbice, and Essequibo provinces. However, the Demerara and Berbice names remained as distinct entities for some time in texts from the era. After 1840, British Guiana’s exports to Britain matched Jamaica’s and continued to climb. By the 1870s, British Guiana was consistently the largest rum supplier of the British empire.

Grenada: In the first half of the 1800s, Grenada regularly exported between 300,000 and 600,000 gallons of rum annually to Great Britain. However, production volumes dropped off in the 1860s.

Jamaica: By the 1700s, Jamaica was the largest producer of British Caribbean rum, far more than any other colony. In the early decades of the 1800s, Jamaica exported between four and six million gallons of rum each year; the island dominated Great Britain’s rum supply until the mid-1800s when British Guiana caught up. By the late 1800s, Jamaica’s exports were roughly half of what they were earlier in the century.

St. Vincent: Between 1810 and 1890, St. Vincent regularly exported more than 200,000 gallons of rum per year, peaking at 550,000 gallons in 1814.

Tobago: The island became a British colony in 1797 and rapidly became a significant supplier of rum to the Crown. Between 1809 and 1835 it regularly exported more than 300,000 gallons per year, peaking at 525,000 gallons in

Trinidad: Trinidad exported small amounts of rum in the 1800s. Not until 1915 did the island’s distilleries began churning out large quantities of rum— nearly one million gallons in 1915. By 1939, if not earlier, Trinidad rum was part of the navy’s rum blend.

TRANSPORT & AGING

Most of the rum arriving in London spent very little time aging in the Caribbean. New-make rum was casked and presumably sent off to England on the next available transport ship. Sugar and cane were called “crops,” implying they were not something stowed away in a Caribbean warehouse.

Evidence of this comes from an 1823 Jamaica Planter’s Guide citing the undesirable outcome of delaying the shipment to Mother England:

The sugar and rum were suffered to remain too long on the estate or barquadier without shipping, requiring sometimes one quarter to make up loss by ullage.

Ullage is a term for empty space in a vessel. In short, delay could cause loss of up to 25 percent of the rum.

Similarly, the 1908 Royal Commission report makes the same point during questioning of a Liverpool merchant dealing in Demerara rums:

What is the average age at which rum goes to the market?

It goes not more than two months after it is made as far as we are concerned. We bring it to this country, and I cannot tell you what becomes of it afterwards, except that we have to provide the buyers with twelve months’ storage.

An 1878 book on ship cargoes also suggests that rum was loaded onto ships during the Caribbean distillation season:

In the West Indies the shipments for rum and sugar are usually from the middle of February to the end of October; the new crop comes in late in February or early in March, when the principal shipments take place.

From this, we can posit that if rum was being aged in the Caribbean for any significant duration prior to sending it to England, the shipments might have been distributed more evenly throughout the year.

Also pointing to a rapid shipment for just-distilled rums: Evaporative losses are significantly higher for Caribbean-aged rums. Rum importers may have preferred their rums to slumber a bit closer to home in a cool vault under the Thames, minimizing the angel’s share and thus maximizing profits. Also, the West India Docks had an elaborate system to securely age rum in a controlled environment. Yet another possible reason for sending rum immediately to London: It made more sense to age where skilled coopers and casks were readily available.

Once aboard a ship, the ocean waves rocked the rum casks back and forth for a month or more. Before the advent of steam-driven transport, a sailing ship typically took at least six weeks to travel from the West Indies to Rum Quay. (The movement of rum within a cask, the extreme humidity, and the weather during the journey at sea affected the rum in ways we are only beginning to understand; Pillar Number 4 in the second part of The Rum Never Sets explains this technical aspect.)

The effect of sea aging was not limited to rum: Norway’s Linie Aquavit is famed for its centuries-old practice of cask aging at sea, a tradition still followed today.

Other surprising factors also impacted the rum’s aging:

The heat from new sugars placed close to casks of rum slackens the hoops, and leakage, of course, ensues. When the head of a hogshead of sugar, with the heading not too tight, has been placed in the hold of a coasting vessel end on to the head of a puncheon of rum, the rum has been drawn through to a depth of two or three inches in discoloration of the sugar. The steam from rum is said to be prejudicial to the health of the crew.

Many weeks after departing the Caribbean, ships full of sugar and rum casks approached England’s southeastern coast and entered the Thames for the final dash to London. Arriving at Blackwall, they entered the West India Docks, where company workers took control of the ship for its stay in the import docks.

Unloading casks required measuring and recording the quantity of rum in each, a process called gauging. Ensuring the Crown got every pence of tax due was of top concern! Measurement was usually via a rod inserted into the bunghole and pressed against the opposing cask wall. The portion of the stick that was wet or dry provided an estimate of the liquid volume in the cask.

Wrap-Up

Chapter Three of The Rum Never Sets also covers the following topics

Plummer & Wedderburn – Mark or Style?

Commercial London Dock Rums

Commercial Navy Rums, which were effectively London Dock rums as well

Finally, a personal note about this book. As an independent rum historian, writer, and educator, most of my income comes from book sales, with a bit more from paid subscriptions to the Rum Wonk Substack. If you enjoy what I’m doing and wish to support my ongoing work, purchasing one my books and/or a paid subscription here is much appreciated.

When you say "land in East London known as the Isle of Dogs. Today, we know the area as Canary Wharf" I'd have say this is incorrect.

The Isle of Dogs is not the same as Canary Wharf. Canary Wharf is located on the Isle of Dogs and whwn people say Canary Wharf, they do not mean the Isle of Dogs, especially those who live in and around the area.