Rum Categories: Where Theory and Practice Collide

A recent post on Reddit about the Smuggler’s Cove book and its rum categorizations inspired me to create this post. I’ll get to the post shortly, but let’s start by briefly reviewing why categories like “white rum” are useless and why modern categorizations also have challenges. For this post, my focus is rum categories as used in cocktail recipes rather than other scenarios like tasting competitions.

Why Do We Categorize Rum – or anything for that matter?

When I cover rum categories in my rum training sessions, I first dwell on why we categorize things in our everyday lives, not just rum.

Fundamentally, we create categories for items like buildings, vehicles, and plants to create useful subgroups. Consider all the vehicles on the road today. We might categorize them using well-understood attributes of those vehicles, including the following:

Function: truck, bus, sports car, SUV, tractor, sedan, etc…

Color: red, blue, green, etc…

Energy source: gas, diesel, hybrid, electric, propane

Which of these approaches is the most useful? That depends on the context. If you’re on a busy street corner waiting for a rideshare, knowing the vehicle’s color is more useful than whether it’s gas, diesel, or electric. But if you rent a vehicle to move your belongings, you care more about its function, i.e., whether it’s a truck versus a sports car. The vehicle’s color is irrelevant.

The key points from the above are:

There are multiple ways to group (categorize) related items

We intuitively select the best categorization for the task at hand.

Any given categorization can be correct yet unhelpful in a particular context.

Existing rum categories are perfect examples.

The OG Rum Categories, i.e., The Bad and the Ugly

Rum’s stylistic diversity is its greatest asset. However, when crafting a cocktail recipe, the creator likely has a specific rum flavor profile in mind. You can’t just use anything labeled “rum” and get the expected result. To avoid such ambiguity, many recipe creators specify the exact rum they use, e.g., “Havana Club 3.”

Unfortunately, Havana Club 3 isn’t available in the US due to the US embargo. A US person looking at a recipe specifying “Havana Club 3” may skip making it because they don’t have it and don’t know an appropriate replacement. There are many good substitutions like Diplomatico Planas, but the typical recipe follower likely doesn’t know these rums are “close enough.” A recipe full of hyper-specific ingredients can inspire fear of “doing it wrong.”

The obvious “fix” here might be to specify a style of rum rather than a specific brand expression. Unfortunately, too many recipes swing the pendulum too far in the opposite direction by opting for ill-defined categories like “white rum.”

The only criterion necessary to be called a “white rum” is the lack of color. The hapless rum novice could plausibly grab a bottle of Rhum J.M Blanc or Wray & Nephew White Overproof as their “white rum.” A recipe calling for “white rum” but made with the J.M or W&N is likely not what the recipe creator envisioned.

Can We Do Better?

Perhaps we might dispense with colors (white, gold, dark) as categories and use something more closely connected to the expected flavor profile. Many years ago, the origin of a rum could usually serve as a strong hint about its flavor profile. In his 1946 Trader Vic’s Book of Food and Drinks, Victor Bergeron went to great length explaining the flavor profiles of “Jamaica rum,” “Puerto Rico rum,” and many more. More recently, Jeff “Beachbum” Berry used similar origin-based descriptors in his seminal Tiki drink books.

However, regional descriptors are far less useful today. Rum made in Puerto Rico now encompasses pot-distilled cane juice from San Juan Artisan Distillers and the traditional “Spanish heritage” column-distilled rums of Bacardi and Serrallés (Don Q.) And while Overproof Jamaican rums like Wray & Nephew White Overproof are full-fledged Jamaican rums, they are very different than the aged rums like Myers’s and Red Heart that Trader Vic considered as the reference for Jamaican rum in the 1940s.

Even “Martinique rum” isn’t always what you think. In my article, Tiki’s Missing Ingredient: “Martinique Rum” of Yore, I detailed how the “Martinique rum” that Don the Beachcomber and Trader Vic used in their 1930s-1960s recipes was molasses rum and closer to Jamaican rum than today’s rhum agricole. While you might enjoy using Rhum Clément VSOP in your Three Dots and a Dash, just know it’s nothing like what Don the Beachcomber used.

Technical Categorizations

In response to the problems of categorizing rums by color, origin, and strength, some of the rum community’s best minds devised alternative ways of categorizing rum. The three best-known categorizations rely on technical details about how the rum was produced:

Gargano Classification – Luca Gargano

Smuggler’s Cove Classification – Martin and Rebecca Cate

The Whisky Exchange Rum Classification – The Whisky Exchange

Production details used in these technical categorizations include source material (cane juice, molasses) and distillation method (batch, continuous, or blend). Some include aging in the criteria (Smuggler’s Cove), while others (Gargano and The Whisky Exchange) don’t. My observations on these categorizations are in Chapter 3 of Modern Caribbean Rum, which is also accessible as an online preview.

While technical categorizations are a clear improvement in some way, the question remains: how do they work in cocktail recipes? Do bartenders (home and professional) find them more useful in selecting a rum that aligns with what the recipe creator envisioned?

Theory vs Practice

Martin and Rebecca Cate’s Smuggler’s Cove book came on the scene in 2016. I was among the first to review the book and heartily recommend it.

All the book’s recipes use the book’s rum classification, which consists of 21 categories, which I’ve represented as seven meta-categories with different aging durations:

Pot Still (Unaged, Lightly Aged, Aged, Long Aged)

Blended (Lightly Aged, Aged, Long Aged)

Column Still (Lightly Aged, Aged, Long Aged)

Black (Pot Still, Blended, Blended Overproof)

Cane (Coffey Still Aged, Pot Still Unaged, Pot Still Aged)

Cane AOC Martinique Rhum Agricole (Blanc, Vieux, Long Aged)

Pot Still Cachaça (Unaged, Aged)

The category differentiators primarily focus on source material, distillation type, and aging duration rather than color or origin. Thus, the book’s Mai Tai recipe specifies “blended aged rum” rather than “Jamaican rum,” as most Mai Tai recipes do. It follows that any “blended aged rum” can be used when making a Mai Tai, and the book lists rums for each of the 21 categories.

The number of rums has exploded in the eight years since Smuggler’s Cove was published. Anyone who understands the Smuggler’s Cove classification criteria and knows some basic details about a given rum’s production can map a “new” rum into the classification. Despite this, the Facebook and Reddit forums are a near-constant stream of posts asking, “What Smuggler’s Cove category does <SOME RUM> belong to?”

Even though the Smuggler’s Cove classification is technically sound, many Tiki enthusiasts struggle to find the information needed to fully utilize the classification, especially when new rums come on the scene. A recent r/Tiki post on Reddit had an excellent discussion about this. It starts:

Subject: Updated version of Smuggler’s Cove’s rum bottle category list?

In Smuggler’s Cove, part three, chapter Understanding Rum, there’s a huge list of all the different bottles organized into SC’s categories. It is now quite a bit out of date and missing hundreds of bottles that didn’t even exist back then. Is there a version of this list out there that is maintained?I find it tedious to look up so many bottles only to find their own website has very little info. Is such and such bottle with “dark” in the name simply a blended moderately aged rum, or is it really a black blended? Or maybe the “dark” is purely coloring and despite it saying “aged” in the name, it’s actually only lightly aged?

I would love to be able to quickly search for a bottle I have only just discovered to quickly find out what kind of rum it really is.

The comments on the post are well worth reading. In particular, commenter u/CityBarman had some particularly keen insights, which I’ve excerpted here:

… any classification system that doesn’t approach the topic entirely by flavor profile will be confusing at best and disappointing at worst, especially to Tiki newcomers.

As a rum nerd I care how a rum is made and what it’s made from. As a Tiki dork, I couldn’t care less how it’s made. I want to know what it’s going to taste like in the cocktails I drink, surrounded by ephemera and shtick. This is the conundrum….

…perhaps sadly, there is little overlap ’twixt the nerds and dorks. While some nerds may show a bit of interest in Tiki cocktails and some dorks may show a bit of interest in rums, I’d guess very few can honestly claim to be both....

Trying to be all things to all people is rarely, if ever, a recipe for success. Most people don’t want to explore that much. They simply want to be provided a recipe that a “professional” guarantees to work. They’re typically upset when a recipe doesn’t work for them. Simply giving readers explicit permission to play and experiment should be enough encouragement for those with the inclination to do so.

To be fair, this criticism isn’t specific to Smuggler’s Cove book. Non-Tiki dorks would have similar issues if using the Gargano or Whisky Exchange classifications.

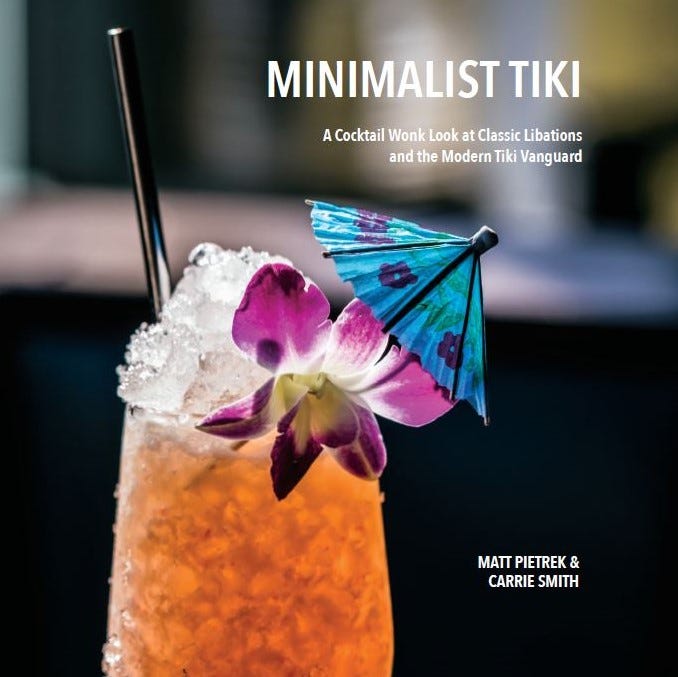

Yet Another Approach – Minimalist Tiki

In 2019, I published my book, Minimalist Tiki: A Cocktail Wonk Look at Classic Libations & the Modern Tiki Vanguard. Seeing the challenges with existing categorizations, I took a different approach that narrowed the scope to the problem at hand. Rather than focusing on how the rum was made, I studied which styles of rum appeared repeatedly in Golden Era tiki drinks of the 1930s to 1960s.

Six styles of rum came up repeatedly. I named them:

Aged Jamaican Rum

Lightly Aged/Filtered Rum

Moderately Aged Rum

Aged Demerara Rum

Overproof Demerara Rum

Aged Agricole Rum

Many of today’s rums don’t fit within these six categories, but encompassing all rums wasn’t the goal.

I somewhat ignored my above point that a rum’s origin doesn’t indicate its flavor. However, during the Golden Era, the available Jamaican and Demerara rums were stylistically closer than today. And while I could have used a name like “funky” instead of “Jamaican,” most people quickly pick up on the core elements of the Jamaican flavor profile, no matter which distillery makes it. You’re also more likely to spot “Jamaica” on a Jamaican rum bottle than “funky” or “hogo.” It was a practical compromise at the time.

Yes, I blew it by adding an “aged agricole” category. At the time, I assumed “Martinique rum” meant rhum agricole, but that wasn’t the case in the Golden Era.

Since publishing Minimalist Tiki, I’ve worked on an improved categorization that encompasses both rums used in Tiki Revival recipes and Golden Era recipes. My latest take on the subject appears in my article, The Nine Essential Tiki Rum Styles - A Beginner’s Guide.

While an improvement over my 2019 categorization, I readily admit that it can’t be all things to all people. My quest continues, but I’m not sure there’s a rum categorization approach intuitive enough for the average cocktail maker to utilize without having a baseline of prior experience working with many rum styles and flavor profiles. With practice, you can look at a recipe and see the creator’s intent rather than just a list of specific ingredients. This ability is what separates practitioners from cocktail masters.

When I first started out in rum I found it very confusing and then took it to mastering Cate's classification system and buying rum in each category. I've since then learned a lot more about Rum and spirits in general and don't pay much attention to any of that. I find rum types a lot simpler than what I was trying to make it. Now I just ask - Is it pot still, column still or mixed? Is it aged or not? Is it funky or not? Is it made from molasses or cane syrup? From that I can get a pretty good idea what it tastes like. I find the generalizations such as Spanish rum, English Rum or French rum not very reliable or consistent. They're more right than wrong but wrong enough to not be useful. The category that I don't find too many people using is sweet or dry. I *really* think this needs to be mentioned just like you would for wine. I wouldn't use a sweet rum where I want a dry one but depending on the flavor profile I might use a pot still rum instead of a column still rum. Sweet/dry is a bigger difference for me and I want to know. Unfortunately most distilleries don't differentiate based on sugar content.

Whenever a friend or family member of mine visits Canada, I ask them to try and bring back a bottle of Havana Club 3.