Rum, Ratios, and Flavor

Editorial aside: I’ve been behind in posting for a month or so, primarily because I’ve been preoccupied with releasing The Tequila Ambassador V.O., our fourth Wonk Press book. With things settled down somewhat, I plan to return to my usual posting cadence.

What follows was originally a large section of a lengthy piece I wrote. However, after reading a draft, a wise friend suggested splitting it into two pieces. Below is the first portion, which focuses on a theoretical approach to aromas and flavors in distilled spirits. This approach has deeply impacted how I think about rum, rum styles, and distilled spirits in general.

Part 2 will be a more specific opinion piece building on the concepts presented here.

Flavor Origins

On the first page of the first chapter of Modern Caribbean Rum, I wrote:

Fundamentally, rum is a type of distilled spirit made from a specific source material. This begs the question: What is a distilled spirit?

It’s instructive to reverse those two words: Spirit. Distilled.

Another word for spirit is “essence.” A distilled spirit is the essence of something, concentrated (distilled) to a purer form. Rephrased, distilled spirits are the purified essence of the raw agricultural material from which they’re made.

By this definition, tasting single malt Scotch should bring barley to mind, tequila should taste like agave, rum should evoke sugarcane, and cognac should make you think of grapes.

While this is true to varying extents depending on the spirit in question, many spirits have flavors wholly unrelated to their source material. Sip a glass of Laphroaig and tell me you notice the malted barley aromas before the peat smoke. Go ahead, I’ll wait.

The same is true for bourbon as well. While the taste of the grains in the mash bill — at least 51 percent corn—is usually somewhere in the mix, nearly everyone first notices the oaky, vanilla flavors that linger on the pallet. While these flavors reach deep into a bourbon lover’s heart, they are far removed from the taste and smell of the source grains.

There are two primary steps during spirits production where they acquire flavor:

During fermentation of the source material, e.g., grain, sugarcane, fruit, agave, etc.

During aging.

(For this exercise, I’m excluding spirits flavored after distillation, including gin and spiced/flavored spirits like Fireball or Captain Morgan.)

What about distillation, you say? Distillation isn’t about creating flavor in any significant way. Instead, distillation filters and concentrates the flavor compounds in the wash after fermentation completes. Distillation concentrates the desirable flavors and filters out the undesirable flavors. However, distilling to too high a strength can reduce desirable flavors created during fermentation.

When it comes to fermentation flavors, think fruity and (sometimes) grassy. Imagine oak, vanilla, cinnamon, and roasted coffee for aging flavors. When a cask is brand new — a requirement for aging bourbon — the wooden staves are a veritable tea bag of oak and vanilla flavors that quickly infuse the spirit.

The flavors from fermentation and aging rarely overlap and are fairly easy to differentiate in a spirit. It’s unlikely you’ll get oaky flavors from fermentation or banana notes from time in a cask.

A musical analogy is useful here. Think of a two-piece band like The White Stripes, where Jack’s guitar playing represents fermentation flavors and the aging flavors are Meg’s drumming. You’re not likely to mistake Jack’s guitar chords for Meg’s drum fills. Jack playing by himself is an unaged rum. Stretching this analogy to the breaking point, just like Jack and Meg can independently play softly or aggressively, fermentation and aging flavors can be independently very soft or very aggressive.

A rum fermented for a day or two using regular “brewer’s yeast” will have far less fermentation-derived flavor than a rum fermented for 3 weeks using dunder, muck, and wild yeast. Think Bacardi Superior compared to Rum Fire or the Haitian clairins.

Likewise, a rum aged for a year in a large wooden vat will have far less wood-extracted flavors than a rum aged for 20+ years in a bourbon or ex-bourbon cask. Think Rhum J.M Eleve Sous Bois versus Appleton Estate 21. In the tequila world, it’s the difference between a reposado and an extra anejo.

Before continuing, it’s important to note that the aging process is much more complicated than extracting flavors from the wood. Certain flavors are transformed, some are intensified due to the angel’s share loss, and others are diminished. We won’t examine all these details here. However, Chapter 8 (Rum Production: Aging) of Modern Caribbean Rum dives deep into all aspects of aging process chemistry.

A Different Way to Think About Flavor

With the above background in mind, here’s how I approach and understand distilled spirits—both within and across categories.

Every spirit possesses some combination of fermentation and aging flavors. Without considering what those flavors are, we can assign values to our perception of the intensity of both types of flavor.

For fermentation flavors, 0 represents pure vodka, i.e., no discernible flavor, while 10 is the most intense flavor you can imagine, such as Hampden Estate DOK.

For aging flavors, 0 means no aging flavor at all, i.e., an unaged spirit. 10 is intensely woody, to the point of being bitter and undrinkable. I’ve tasted certain rums aged for 30+ years that aren’t pleasant to drink and approach a 10 on the scale. To my palate, the typical 10+ year aged bourbon is around 6 on the scale.

These intensity values imply nothing about what the flavors are, just how intense they are. Taylor Swift, Mötley Crüe, and the London Philharmonic sound very different, but all can be played softly or at an earsplitting volume. Also, intensity values vary from person to person and aren’t strictly linear. Think of them like the volume control on your TV/stereo/mobile device. One person’s intensity ‘4’ may be another person’s intensity ‘6’, and that’s OK.

Once we’ve established how intense the fermentation and aging flavors are — per our personal and subjective criteria — we can also compare them to each other. If the fermentation intensity is substantially more than the aging, we can say the spirit is fermentation-forward. Likewise, if the aging intensity is much larger than fermentation, we can say the spirit is aging-forward.

Fermentation-Forward and Aging-Forward Examples

Fermentation-forward spirits typically utilize a relatively long fermentation duration and have little or no aging. Prime examples include unaged Jamaican overproofs, unaged cane juice spirits like “blanc” rhum agricole, Rivers Royal from Grenada, grand arôme, and clairins like Le Rocher.

Yes, there are rums with a fair amount of aging flavor that still qualify as fermentation-forward. Consider Hampden Overproof, Hamilton Jamaican Pot Still Blonde, and Rum-Bar Gold. The aging notes are there but lurking in the background.

Aging-forward spirits achieve their dominant flavors from time in a cask. Putting aside the white rum subcategory for now, nearly all Spanish Heritage rums are aging forward. Many rum aficionados dismiss Spanish Heritage rums as bland and uninteresting, but these rums intentionally cater to the preferences of the drinking population from which they originate. As a style, Spanish Heritage rums are no less valid than the wild Jamaican hogo bombs.

The hallmarks of the classic Spanish Heritage style are:

A relatively short fermentation period

Distillation of some or all of the spirit at high strength (>90% ABV)

Significant development of wood-derived flavors during aging

Well-known examples of aging-forward rums include Bacardi Ocho, Flor de Caña 12- and 18-year, Havana Club 7, Brugal 1888, and Santa Teresa 1796. One of the signature notes of Spanish Heritage rum is roasted coffee beans. I particularly pick up that aroma in Flor de Caña expressions.

What about traditional “white rums”? Or, as I prefer to call the category, “lightly aged and filtered rum?” This style is characterized by relatively light fermentation and aging flavors resulting from short fermentation and high-strength column distillation. Bacardi Superior, Havana Club 3-year, Tanduay White, and Flor de Caña 4 Extra Seco are emblematic of the style. I’d be hard-pressed to call such rums either fermentation-forward or aging-forward.

Naturally, some rums are well-balanced between fermentation- and aging-derived flavors. A good example is the lightly aged rhum agricoles of Martinique and Guadeloupe. Look for expressions labeled élevé sous bois (aged at least 12 months in oak containers) or VO (aged at least 3 years in oak casks no larger than 650 liters.) Some of Renegade Rum’s current Cuvée series also exhibit a good balance between fermentation and aging flavor.

In general, if a rum has a healthy dose of pot distillate and ages for 4 years or less in ex-bourbon casks, there’s a reasonable chance it has both fermentation and aging flavors in roughly equal proportion. Likewise, a column-distilled rum can achieve a similar balance if it starts a flavor-packed wash and distillation doesn’t go above 85% ABV or so.

To the Charts!

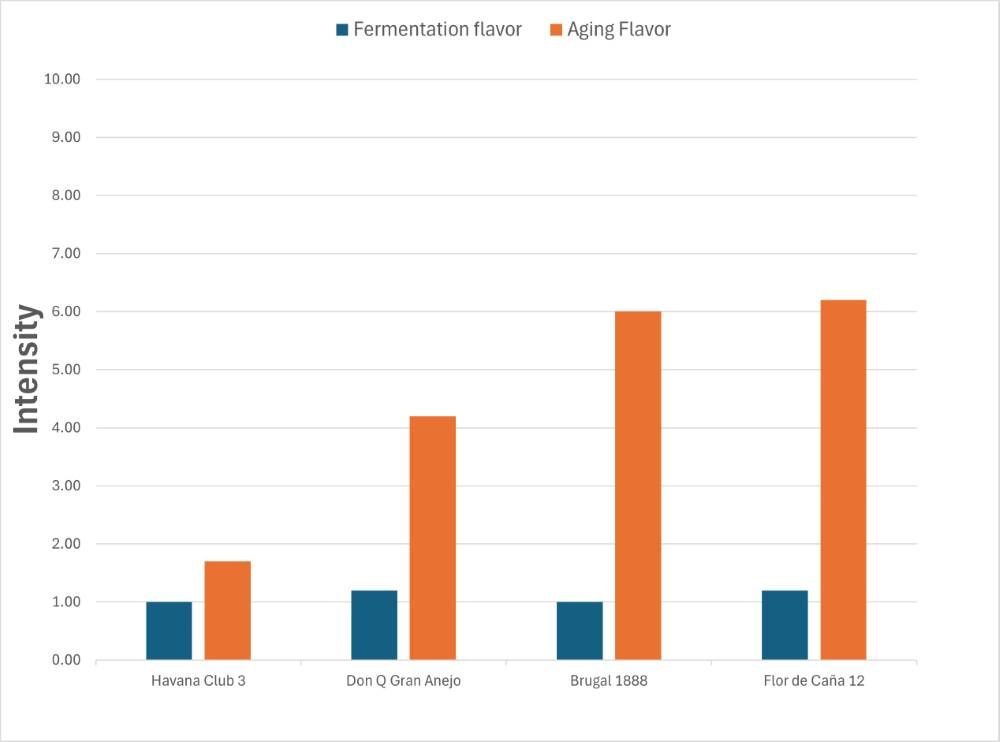

I’ve made a few charts to illustrate the above concepts visually. In these graphs, The Y-axis (intensity) goes from 0 (vodka / no aging) to 10 (hogo monster extraordinaire / way over-oaked and bitter). Reasonable people may disagree with my intensity value choices, but the overall point stands.

Wrap Up

What I’ve written above isn’t particularly advanced or radical. However, it outlines an approach to evaluating a spirit that few reviewers utilize. By intentionally focusing on a spirit's flavor intensity rather than specific flavors, the intent of the spirit’s creators comes to the front. For example, is preserving the flavors of the source material most important? Is the distillate just a substrate to layer on aging-induced flavors? Or is the distiller/blender looking to create a symphony of different types of flavors?

The above also provides a mechanism for grouping spirits with radically different tastes but a similar ethos in how they’re made. For example, unaged Jamaican overproof rums like Rum Fire, Rivers Royale, Savanna Lontan, and Clairin Le Rocher are all playing a very similar game, i.e., intense flavor with no concession to tempering things via aging. Likewise, bourbon is an aging-forward spirit that invites comparison to certain aging-forward rums. We’ll explore this topic in a subsequent post.

Well written and succinct. Good intro to what is a very complex subject.