The Myth of Royal Navy Rum and the Gunpowder Test

One of the oft-told, erroneous tales about Royal Navy rum is that Britain’s navy used the “gunpowder test” to test a rum’s strength before the invention of the Sikes Hydrometer in 1816. As the story goes, if rum-soaked gunpowder would “flash” after it was exposed to a flame, it was at least proof strength, i.e., 57% ABV in modern units. This allegedly ensured that sailors weren’t given rum at less than official issuing strength.

A brief spin through history casts very serious doubt on whether this really happened.

While the “gunpowder test” was a thing very early on in some circles such as the spirits trade, by the time the Royal Navy had settled on rum as their official spirit, they were already using hydrometers to test alcoholic strength.

For those unfamiliar with hydrometers, they somewhat resemble a large thermometer that floats in a cylinder filled with the spirit to be tested. Markings along the hydrometer enable the alcoholic strength to be estimated.

The First Hydrometer

While Bartholomew Sikes is the name commonly associated with the hydrometer, he wasn’t the first to market one—not by a long shot.

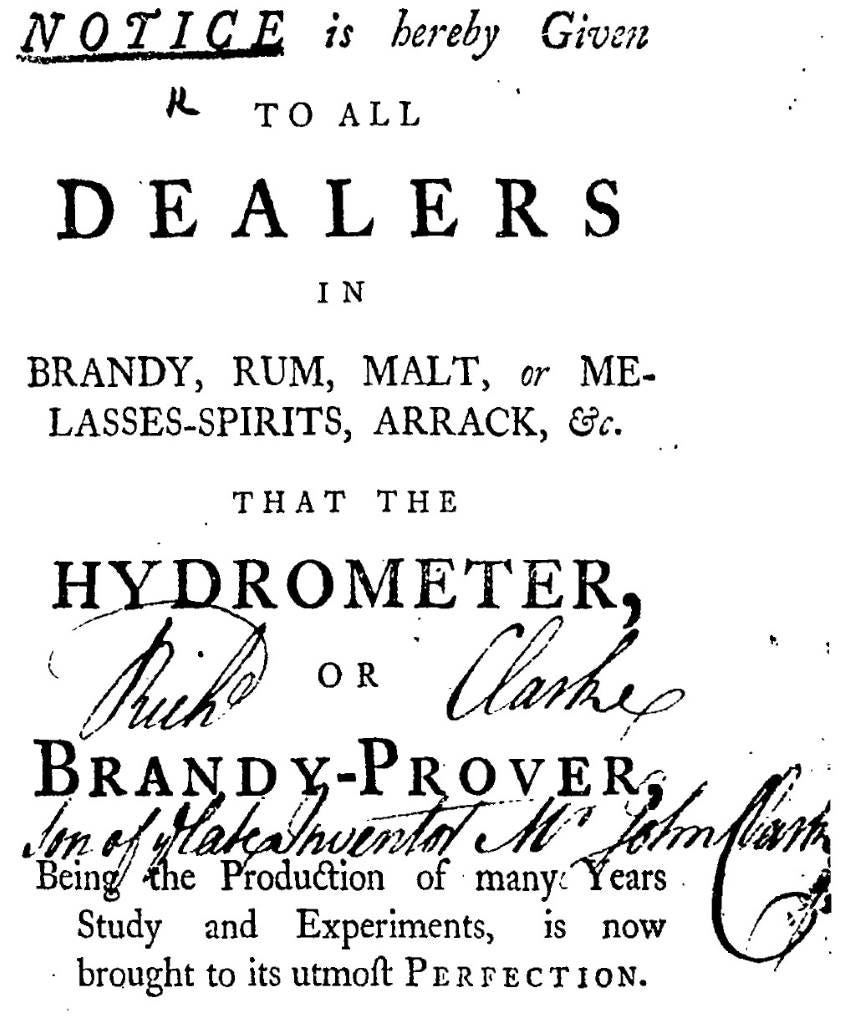

Prior to Sikes’ arrival on the scene, the British standard of measure was Clarke’s Hydrometer, invented around 1730 and refined several times. In a 1746 advertisement, inventor John Clarke declared his hydrometer to be perfected. Below are snippets from Clarke’s advertisement.

In the late 1700s, Clarke’s hydrometer became the official standard of measure for British excise collectors and the Royal Navy provisioners, as noted later in the advertisement:

…is made Use of by the Honourable Commissioners of his Majesty’s Victualling - Office, in Ascertaining the Strength or Proof of those Large Quantities of Brandy they purchase for the Use of the Royal Navy.

Note well, the text says brandy, not rum. The Royal Navy defaulted to issuing brandy early on and didn’t adopt rum as its only issued spirit until the early 1800s.

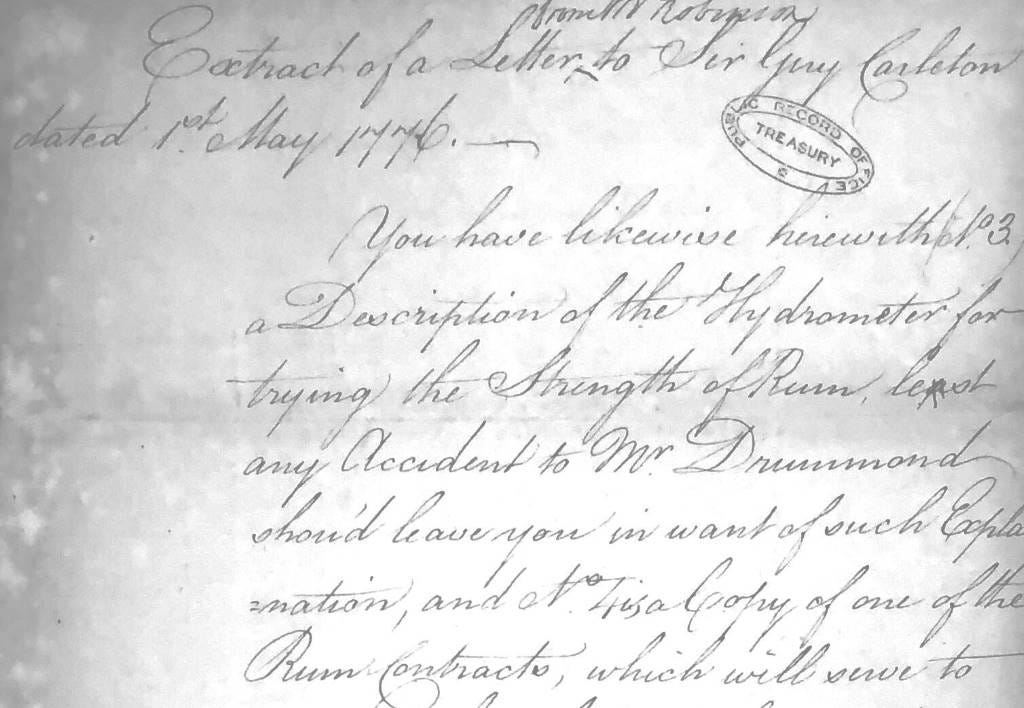

We also know the Royal Navy was using hydrometers in the field as early as the American Revolution — a 1776 letter to Guy Carleton, the last British Army commander during the American Revolution, mentions a hydrometer:

You have likewise herewith at No. 3 a Description of the Hydrometer for trying the Strength of Rum, lest any Accident to Mr. Drummond should leave you in want of such Explanation.

Unfortunately, Clarke’s hydrometer was extraordinarily finicky and prone to false readings and required adding numerous weights depending on ambient conditions such as temperature.

This is where Sikes, a British excise officer, enters the picture. In 1802, British authorities initiated a competition to find a simpler and more accurate hydrometer. Sikes’ hydrometer won the competition, but he died suddenly weeks afterward. Sikes’ widow and son-in-law continued to press for its official acceptance as the new standard of measurement, which the British Parliament finally granted in 1816.

About that Gunpowder Test

Bringing this all back to the apocryphal story of the Royal Navy gunpowder test for rum, it seems clear that hydrometers were far more reliable than igniting gunpowder to ascertain alcoholic strength. In all my years of research into the Royal Navy’s rum tradition using original source documents, I have yet to find any mention from a 1700s- or 1800s-era source describing a gunpowder test onboard a ship.

Furthermore, from 1866 onward, the Royal Navy issued rum at less than proof strength, meaning the gunpowder test would always fail. For more on this part of the story, see this earlier article, Navy Rum Strength isn’t 57%.