This Man Saved the Royal Navy’s Rum Recipe

Early in my rum immersion, I became fascinated by the story of Royal Navy rum. My curiosity was less about its consumption and more about what was in it. It was a decade before I ventured into archival sources to learn the real story. In those early years, all I could find about the navy’s rum was from rum bloggers and the occasional book like James Pack’s Nelson’s Blood.

The common denominator in what I found was that Royal Navy rum was a blend of rums from Jamaica, British Guiana, Trinidad, and Barbados. However, all these regions make a wide variety of rums, so just listing each region does not a recipe make. This didn’t stop a few brands from marketing “navy style” rum based on little more than these incomplete details.

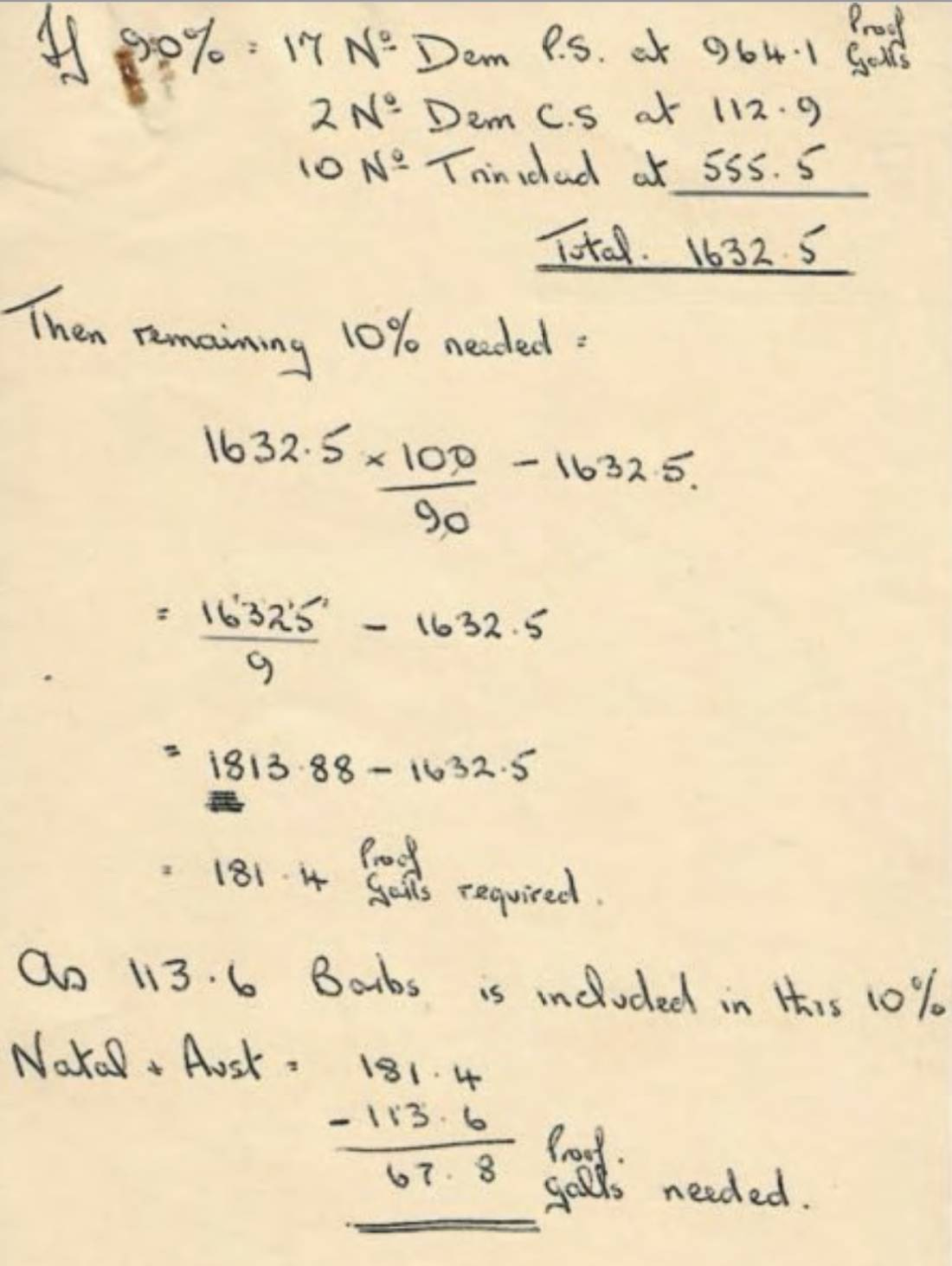

When I later started digging into navy rum records in earnest, I came across additional details, like the following from the Royal Navy’s 1939 victualling manual:

Navy Rum is purchased in the open market upon sample. It consists of a blend of West Indian (mainly Demerara and Trinidad) with proportions of Natal and Mauritius Rums.

While this is somewhat more helpful than a vague reference to ‘a blend of rums from the British West Indies,’ it raises new questions. What are Natal and Mauritius doing here?” And why aren’t Jamaica and Barbados listed? Did countless books and articles have it all wrong?

Yes and no. During the 20th century, the origins of the various rums in the navy blend changed early and often. However, Demerara rum consistently accounted for the largest share of the blend. But while ratios and percentages are nice, they’re still not a recipe that you could make to exactly reproduce what the navy made.

Finding the exact rums used and how much of each became my personal grail. However, the longer I looked, the more I despaired that a complete recipe as used by the Navy was still in existence.

A Fortuitous Encounter

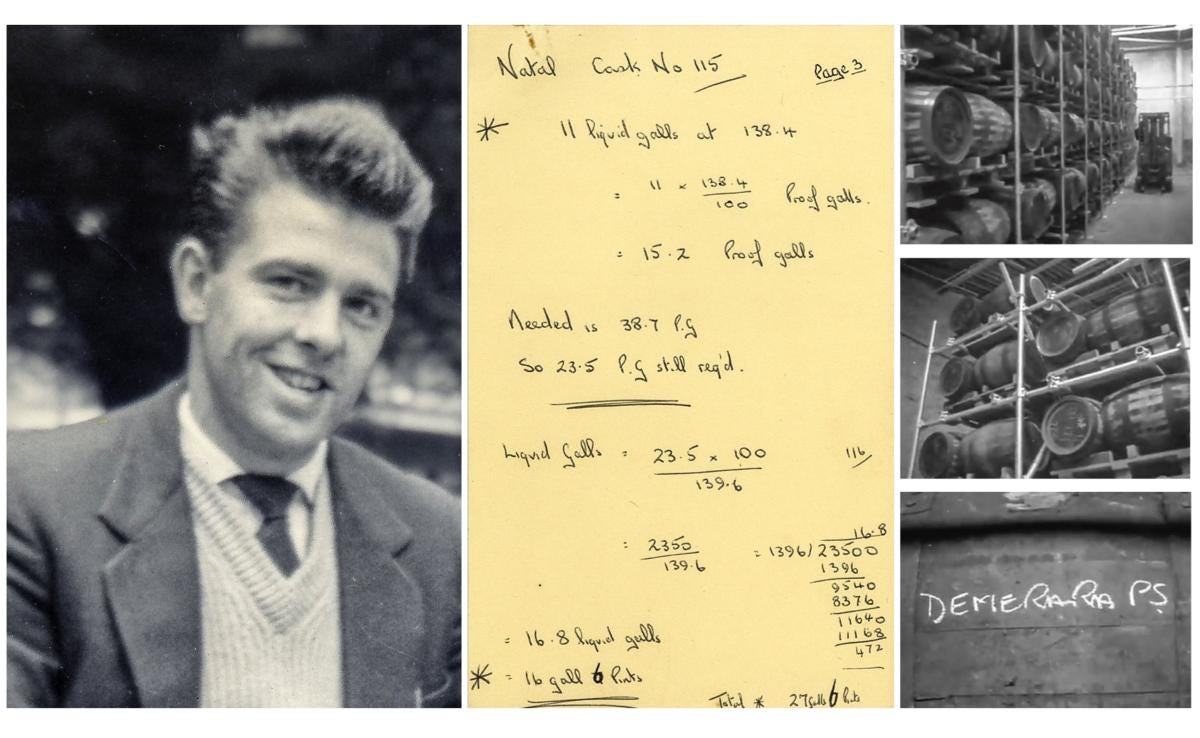

In September of 2023, a gentleman named Arthur Roberts commented on an article I’d written a few years prior:

I was in fact a storehouseman in the Royal William Victualling Yard Plymouth during the 1950’s and 1960’s and at one time I was in charge of the receipt of strong rum and the subsequent blending and revatting of this before issue to the Royal Navy. I still have in fact my handwritten calculations of the first vatting I did, detailing the amounts and percentages of each variety of rum required.

My eyes went wide as I read it. Could Arthur really be sitting on the recipe I’d spent years hunting? I quickly emailed him and tried to keep my hopes in check as I awaited his reply.

Our initial emails soon led to a phone call. Early in the call, Arthur began reading from his handwritten calculations. I knew I’d found my grail when he read off, “17 casks Demerara P.S.” and “2 casks Demerara C.S.” (P.S. and C.S. referring to pot still and column still, respectively.)

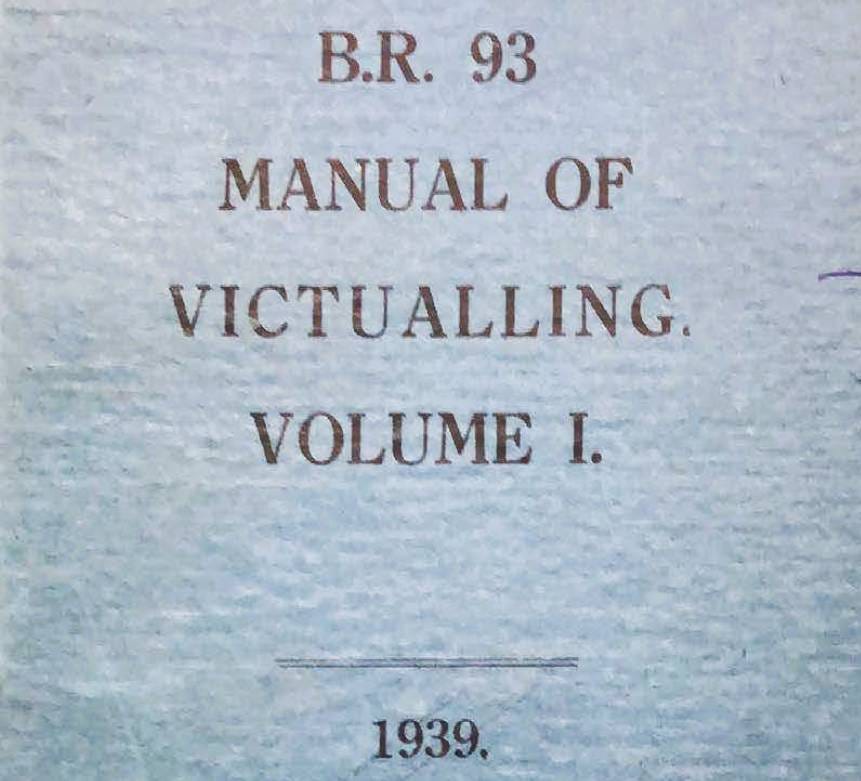

When our interview concluded, I asked Arthur to send me picstures of the pages. What arrived was 10 pages of notes, nine handwritten on yellow paper. My jaw dropped; within those pages were other details I’d never imagined. They didn’t contain the specific marks used, as the navy didn’t label their casks with marks. But when combined with other information I’d found, there was enough detail to make a very strong guess about which rums were used.

Given the importance of these documents, I asked Arthur to have them professionally scanned. A portion of the scans is included here. To be clear, Arthur’s notes represent just one moment in Royal Navy’s 200+ year history. Nonetheless, they are the most detailed account of a Royal Navy rum recipe ever publicly shared.

More of the scans, along with further details about the exact source rums and my interview with Arthur Roberts, can be found in The Rum Never Sets book.

Excerpts from Arthur Roberts Interview — The Rum Never Sets

MP: Which victualling yard did you work in?

AR: Technically, the Royal William Victualling Yard in Plymouth. The Royal William Victualling Yard was a big granite yard, dockside in Plymouth. However, the rum store was at a sub-depot at Wrangaton. [Note: Wrangaton is about 30 km east of the main victualling yard.]

The main depot stores in Plymouth were becoming unfit for modern use; the forklifts couldn’t go on the upper floors because they were wooden. They were gradually moving some stores out to purpose-built outlying depots.

MP: How did the rum arrive at the vatting facility?

AR: We had a supply of rum from the bonded warehouse, and it was brought to us by the appropriate customs officials. When we received strong rum, they would wheel in the barrels, which were marked either Demerara, Trinidad, or Barbados.

When I started in the store, I thought, “This is taking ages,” getting the pipette to fill and filling the measure jar. As a young brash boy, I thought, “We’ll siphon it out.” I got a bit of plastic piping and put it in the barrel and took a nice big suck to start the siphon off. You can guess what happened. I took a big mouthful of 130, 140 proof rum. I got caught and spluttered, and everybody fell about laughing. It was my first experience of strong rum. I never did that again!

MP: What information were you given about the rum in the cask received from customs? Did you know what was in each cask beyond just where it came from?

AR: Just the country.

MP: Did the Royal Navy have an official document with the recipe that was distributed to each victualling yard?

AR: I can’t recall seeing anything like that in a manual.

MP: Walk me through the steps of a single vatting.

AR: In the store, we had racks of the different rums from Demerara and Trinidad to Barbados, Natal, and Australia. They were kept separate in different parts of the store.

When we vatted, we first needed seventeen barrels of Demerara rum. So, we wheeled out seventeen barrels, tipped them in the vat. Then the barrels of Trinidad rum; wheel them out, tip them in the vat. Two barrels of Barbados rum; wheel them out, tip them in the vat. There was also a percentage of Natal and Australian, which we had to calculate—it was a small amount.

We had to get the strengths and number of liquid gallons, then work out how much water was required to bring the vat down to navy issuing strength, which was 95.5 [proof] in ten-gallon barrels.

MP: Were the one-gallon packing samples the same as flagons?

AR: Yes. They were earthenware jars, which were encased in wickerwork. We didn’t do many one-gallon jars because I think they only went to submarines. I think the kilderkins would’ve gone to a bigger class of ship in order to get them down the gangways and the stairwells and everything into their storage departments. The jars were filled at a slightly different strength than the barrels. They were normally sealed with the red sealing wax and a stamp put on it—RWY, Royal William Yard.

What About Charles Tobias and Pusser’s Rum?

Some of you may recall that in the late 1970s, the Royal Navy gave Charles Tobias the recipe so that he could make and sell Pusser’s rum. Charles lived for nearly 50 years afterwards, and I was fortunate to interview him in 2020. I did get a few tidbits from him — Port Mourant and two Caronis were in the recipe, but he didn’t volunteer everything, nor how much of each. While the navy’s recipe might still be found in Pusser’s company records, I don’t expect it ever to see the light of day. And with Tobias’ recent passing, I can no longer revisit the topic with him.

A Note for the Coming 2025 Holiday Season

Sharing stories like the above is one of the joys of my career as an independent writer, publisher, and rum historian. Research like this takes time, money, and the occasional miracle.

I left my software development career in 2018 to learn as much as possible about rum and share what I found with fellow enthusiasts. The time I used to spend in a salaried job now goes towards writing and publishing books, as well as creating deep-dive content for this newsletter.

While Rum Wonk is free to read, there are paid subscription options: monthly, yearly, and founder levels. I’m very appreciative of everyone who’s elected to be a paid subscriber. Of course, more paid subscribers help keep my keyboard humming. Hint, hint!

If you’re looking for something with a more physical presence, Wonk Press books make great gifts! Purchasing Wonk Press books directly supports a small company, contributes directly to our bottom line, and enables us to create more books in the future!

Thanks for reading!

What a freaking coup to find this!!!! Holy smokes and grails, Batman!

Fascinating post. I need to get into the book when my eyes are cooperating. Looking forward to it. The Natal rum and reading up on that was fascinating. I hope one day to visit SA. Cheers Matt!