When is a Column Still Not a Column Still?

After reviewing the medalists from a recent spirits-tasting competition, I was left scratching my head. In this competition, some categories were differentiated by the distillation methodology, e.g., “pot,” “column,” or “hybrid.”

What struck me was that several “column distilled” medalists come from distilleries that don’t appear to have a column still, as the term is generally understood.

I’m not implying anything nefarious is afoot here. Rather, it highlights a basic point of confusion about the two fundamental modes of distillation: batch and continuous, not pot and column as many people think.

To momentarily jump ahead for those versed in distilling, a still with a plated column doesn’t necessarily make it a “column still” as the term is conventionally defined.

What follows is a high-level overview of distillation modes and their associated still types. It’s not a deep technical explanation and purposefully oversimplifies certain details for brevity. If you’re looking for a distillation deep-dive, I suggest the distillation chapter of the Modern Caribbean Rum book.

What is Distilling?

Fundamentally, distillation is about separating desirable molecules in a liquid from undesirable compounds. For potable distilled spirits, certain molecules like ethanol, esters, and aldehydes are desirable, while other molecules like methanol and water (to some extent) aren’t desired.

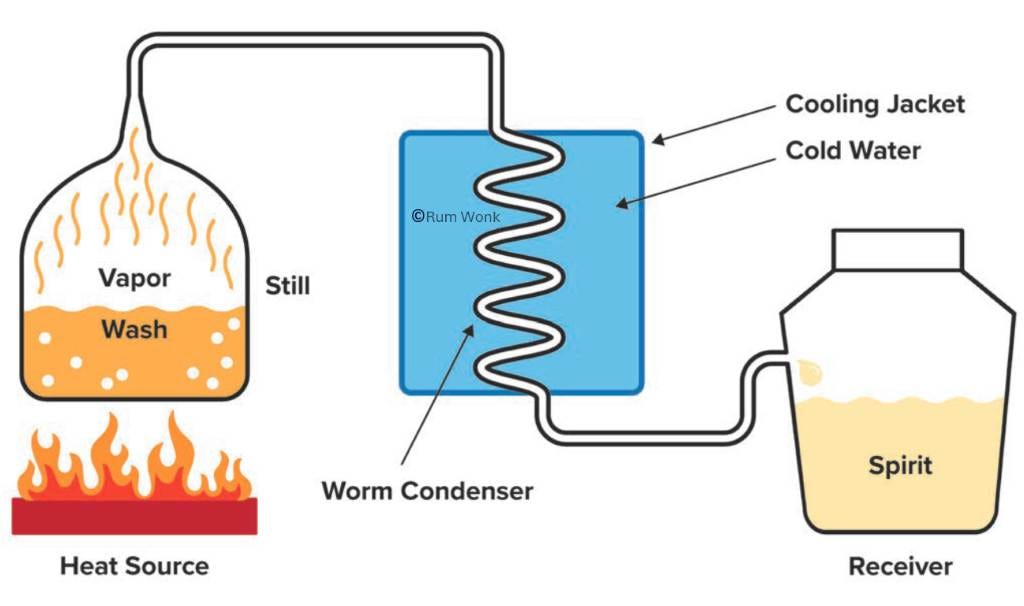

Both batch and continuous distillation rely on heating the liquid to be distilled, i.e., the fermented wash. When the liquid boils, the molecules with lower boiling points turn into vapor, while molecules with higher boiling points remain in the liquid.

This vaporization and subsequent condensation back into liquid is the bedrock principle underlying how distillation separates different types of molecules within the fermented wash.

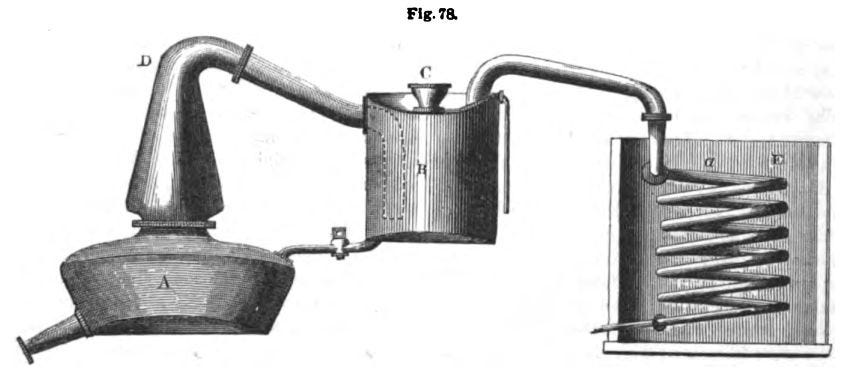

Before the early 1800s, nearly all distillation utilized a simple metal pot (or kettle) topped and sealed by a swan neck. The vapors passing through the swan neck eventually pass through a cooling section, typically in a water bath, which returns the vapors to a liquid state. The cooling section is called a condenser.

With this setup, separating the desirable and undesirable liquids is just a matter of directing the condensed liquid into two or more buckets. The desirable bucket contains the “hearts,” while the undesirable bucket(s) contain the “heads” and/or “tails.” This process is usually called pot distillation because it involves a pot. However, a more concise description is batch distillation because it’s done one batch at a time. Batch distillation is time-based, as what comes from the still changes from moment to moment during distillation.

A simple batch distillation like the one described above usually isn’t sufficient to obtain the desired alcoholic strength and purity. However, you can take the desirable liquid obtained and distill it again. This is called “double distillation,” and it’s how nearly all distilled spirits were made until the 1800s. By law, single-malt scotch whisky and cognac continue to be made this way today. (Yes, some spirits are single-distilled, but it’s not germane to the discussion.)

Evolution

In the early 1800s, some clever folks in Europe created a shortcut to avoid distilling everything twice. Their trick was to do both distillations concurrently. Rather than connecting the first pot still’s neck to a condenser, it instead feeds into a second distillation chamber. This second distillation chamber is called a retort. The liquid in the retort completely covers the outlet of the incoming pot still neck. The retort also has an outlet pipe that passes through the condenser to cool the vapors back to liquid.

During distillation, the pot still’s vapor flows into the liquid of the retort. Because the incoming vapor is hot, it boils the liquid in the retort. The vapor rising from this second boiling flows through the output pipe to the condenser. While a pot still with a retort is more complicated to construct and operate a simple pot still, it can create a finished spirit within a single distillation pass.

If one retort is good, two retorts might be better! By adding a second retort into the pipeline, the distillation has three distinct vaporization/cooling sequences. Such stills are called “double retort pot stills” and are the most common batch stills found at large Caribbean distilleries.

Continuous Evolution

Concurrently with the evolution and adoption of retort pot stills, other clever minds invented a way to avoid distilling one batch of wash at a time. That is, a way to continuously process an incoming stream of fermented wash into a finished spirit. The invention of continuous distillation revolutionized distilled spirits production around the world. The name most associated with it is Aeneas Coffey, for whom the Coffey still is named.

The core concept of continuous distillation involves linking dozens of distillation chambers together in a sequence. The physical implantation is a vertical tube with dozens of horizontal “plates” spaced at consistent intervals. Each plate is perforated with numerous openings through which liquid and vapor can flow in either direction.

Such stills are traditionally called column stills, or more formally, continuous still or continuous column still.

During distillation, continuous streams of fermented wash and steam feed into different locations in the column. After the startup phase, each plate becomes covered with a layer of liquid. While gravity wants to pull the liquid down through the openings, it’s counterbalanced by hot vapor rising from the plate below, pushing upward through the openings and into the liquid. (As noted above, this is an oversimplification, but roll with it.)

Each plate in the column functions as a crude distillation chamber, with the liquid on each plate having a slightly higher ABV than the plate below. It can be hard to visualize this, but column stills “sort” and distribute the incoming molecules across the column’s interior in real-time. The heavier molecules migrate to lower plates in the column and the lighter molecules migrate to the uppermost plates.

Somewhere along the column is a plate (or plates) best suited to slowly and continuously draw off liquid for collection. The distiller decides which plates to draw from. The lower the plates, the heavier the resulting distillate will be.

The essential point with column distillation is that where the liquid is collected from matters, not when, as in batch distillation.

Continuous distillation is more mechanically complex than batch distillation, but once set up can operate nonstop for days, weeks, or months. It’s also much less expensive to operate than batch distillation, per unit of wash processed.

Operating a column still requires distilleries to have a battery of fermenters operating round-robin style to ensure a steady stream of input to the still. Due to their cap-ex cost and operational demands, very few “craft” distillers use continuous distillation.

Intermediate Recap

To briefly recap before pressing onward:

Batch distillation uses pot stills, possibly with retorts, to process one batch at a time. Batch distillation is time-based, i.e., what emerges from the still changes over time.

Continuous distillation uses a plated column to continuously process a steady stream of fermented wash. Continuous / column distillation is location-based. Where you collect from matters, not when.

Neither is superior. However, the two approaches can yield noticeably different flavor profiles from the same inputs. A side-by-side comparison of rum from the Enmore (continuous) and Port Mourant (batch) stills at DDL in Guyana provides a vivid example.

The Distillers Speak

For nearly two centuries, “column still” and “continuous still” have effectively been synonymous in the distilling world. To help validate this assertion, I posed a question to four Caribbean distillers:

If you were told a rum was “column distilled,” would you assume it was continuously distilled?

Each of them has decades of experience with batch and continuous distillation at high-volume distilleries. All replied in the affirmative.

I bring this up because “column still” and “column distilled” are often used to describe how a particular spirit is made. The phrases are also used to assign a rum to a category—whether in formal classification systems or in spirits‑judging competitions. Unfortunately, there’s been a rupture in what “column still” means in recent years.

Enter the Hybrid Still

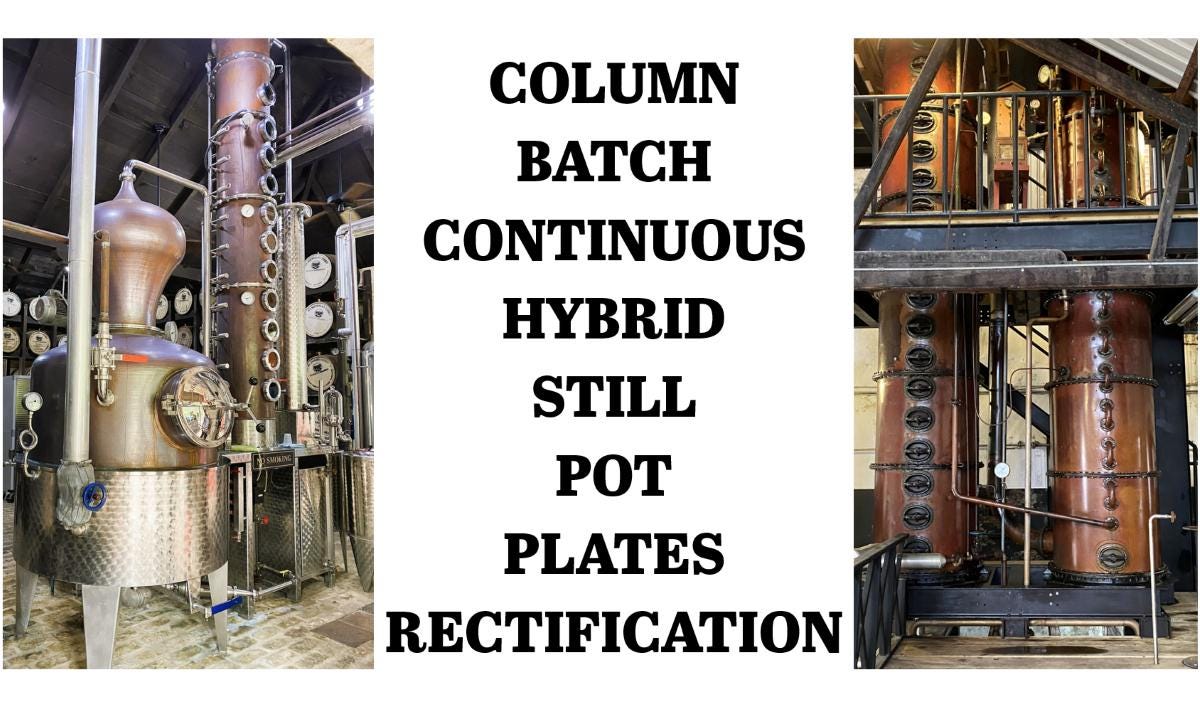

While invented to enable continuous distillation, a plated column can be used with batch distillation.

Recall that retorts were added to pot stills to add additional vaporization/condensing cycles into a distillation. Replacing the retorts with a short, plated column can have a similar effect. Each plate acts like a small retort, albeit with much less purification power. But with enough plates, a spirit in the 90+% ABV range can be achieved.

In some configurations the column section is mounted directly atop the pot still. In other configurations, the column section is physically separate, with the pot still neck connected to the base of the column section. For this discussion, the distinction doesn’t matter.

A pot still feeding a plated column is called a hybrid still. While this term suggests a combination of pot (batch) and column (continuous) distillation, hybrid stills are fundamentally batch stills:

They do not operate continuously like a column still.

They require a pot to function.

The collection (heads/hearts/tails) is done over time, just like other types of batch stills.

The spirit isn’t drawn from specific plates, as with true continuous column stills.

None of the above is intended to speak pejoratively of hybrid stills. They offer tremendous flexibility to smaller distillers, and many highly regarded spirits are made with hybrid stills.

The Takeaway

With the craft distillery count booming recently, hybrid stills are almost de rigueur. However, with this comes a muddying of the waters regarding how distillation and the resulting spirits are described and categorized. I’ve personally seen many small distillers indicate they use a column still when, in reality, they have a hybrid still. One recent competition medalist’s “column still” was a pot topped by a three-plate rectifying column.

I get it; pot still and column still are deeply entrenched in how we describe distillation. Hybrid still is much less entrenched, and requires a somewhat deeper understanding. Nonetheless, a batch still with a column section doesn’t make it a column still by the conventional understanding.

What’s particularly baffling is that in competitions with distinct categories for pot, column, and hybrid distillation, some hybrid spirits somehow wind up in the column still category. It’s perfectly OK to say something is a “hybrid still.” Or, if for some reason that’s not an option, “pot still with rectifying column” is more accurate than “column still.”

You might think I’m tilting at windmills here, but facts matter. Accurate information is important to consumers who spend their money on premium-priced spirits. Likewise, it diminishes the value of tasting competition results when some entrants aren’t placed within the appropriate category.

Very interesting Matt. In my mind I always viewed it as pot, column and continuous.

I'm sure you are correct. As a craft distiller I don't come across many "column stills" here in the UK.

Interesting read!!

But what does “column distilled” really tell me about the rum as a consumer? You said, “ Continuous / column distillation is location-based. Where you collect from matters, not when.”. Shouldn’t the location drawn from be noted on the bottle then? Can we assume it was taken from the top plate unless otherwise specified?