Minimum Age Statements – Can We Do Better?

Among the most sacrosanct tenets in the distilled spirits world is that an age stated on a label means every drop in the bottle aged for at least that duration. In industry parlance, this is known as a minimum age statement.

Thus, if a blender took a cask of 20-year aged rum and added one drop of 2-year aged rum, the result could only say “Aged 2 years.” It’s a very simple concept to understand, explain, and follow.

But what if we stood back and took a hard-eyed look at minimum age statements? Do they have any drawbacks? I can hear the cries of “Heresy! Burn him!!!” already. I understand the sentiment. But rigorously working through the ramifications of minimum age statements and their alternatives is a teachable moment, and I’m all about that.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting any country’s labeling regulations should be disregarded, or that minimum age statements should be thrown on the ash heap. But it’s interesting to ponder their good and potentially not-so-good aspects and see what a different age calculation might bring to the table.

Why Age Statements?

Fundamentally, consumers like age statements because they connect two things important to them:

A simple metric regarding the (presumed) quality level of the bottle.

Some assurance they aren’t being lied to regarding the metric representing the (presumed) quality level.

From the average consumer’s perspective, the longer a spirit ages, the better it is. When applied to a specific brand, this seems to make sense. Guyana’s El Dorado Rum has mainstream rums aged 3, 5, 8, 12, 15, and 21 years. Most people will implicitly assume that:

All El Dorado rums are aged in a roughly similar manner.

El Dorado 12 is “better” than El Dorado 8 because it aged longer.

These notions are not unique to rum. You’ll also find them in bourbon, Scotch whisky, and cognac.

The reality is far more complex. As the saying goes, “Age is just a number.” An age statement is a one-dimensional value whose relevance to a spirit’s quality can be wildly overstated. This is especially true when attempting to evaluate age statements from different brands.

Different Deceptions

Before continuing, let me state up front: three different but related aging topics are at play in this space.

The first is brands using large numbers on their bottles to confuse consumers and retailers into thinking the spirit has aged for that many years. (I’m looking at you, 23.) If you examine these labels carefully, you’ll find that they rarely use specific wording like “Aged 23 years” that would constitute an official age claim in the eyes of a regulatory agency.

The second topic concerns true solera aging, i.e., solera as practiced in Spain. There’s nothing fundamentally wrong with solera aging. It’s only when a brand states or implies an age statement, e.g., “up to 40 years,” that things get dicey.

The third topic is the authenticity of an age statement where the bottle clearly states that the contents aged for the specified duration. For the purposes of this story, I’m focused exclusively on this topic, although the other two are worthy of detailed examinations as well.

What An Age Statement Can’t Tell You

The only thing we know from a minimum age statement like “Aged 7 years” is how long the rum rested in some type of container, presumably a wooden cask.

Now, consider the following information relevant to a spirit’s aging that this one number can’t tell you:

How “fast” was the aging? Was the aging in a hot climate like the Caribbean or a cool, temperate climate like northern Europe? It’s an oversimplification to say that spirits age faster in warm environments, but we can reasonably say that some aspects of the aging processes occur faster when it’s warm.

A well-known case in point: many independent bottlers source their rum from casks aged by The Main Rum company in Liverpool. As a recent multi-bottle release set out to investigate, A Jamaican rum aged for 14 years in Liverpool will be substantially different than the same distillate aged for the same duration in Jamaica,

What was the condition of the cask? Unlike bourbon, which must age in new oak barrels, most rums age in previously used whisky barrels. Newly-made casks have lots of vanillin and other compounds in the wood that leach out into the spirit and help flavor it. The longer a cask holds a spirit, the less flavor the cask will impart via extractive aging. However, other aging processes known as oxidative aging will occur in a cask regardless of the cask’s age. (See Note 1 at the end for a reference to where to learn more about the distinction.)

What strength was the rum put into the cask? The rate of wood extraction and angel’s share loss depends on the strength of rum in a cask. Successful distilleries can afford enough casks to age their rum at the ideal strength for their house style. But diluting rum to the ideal aging strength means more casks are needed, an expense some distilleries can’t afford. If these distilleries age at a higher strength, they risk over-extracting undesirable flavor compounds.

How big was the cask? The larger the cask, the less contact between the spirit and the wood. The result is less extractive aging over the same period. While most rum ages in ex-bourbon barrels, it’s not uncommon to find much larger casks, such as sherry butts, in use.

Sure, a forward-thinking producer could provide the above information, but few do. It’s not hard to imagine that a 5-year rum aged in a new cask in the Caribbean could exhibit more aging influence than the same rum aged for 10 years in an old cask in northern Scotland.

Age is but a number.

Would You Rather…?

Master blenders are rightfully heralded for creating a symphony of flavors from different source rums. These source rums might vary substantially in how they were distilled and how long they aged. We sometimes hear stories of a particular expression magically coming together by adding a small amount of one final rum. With that in mind, consider two scenarios:

A blend where each rum aged for exactly 10 years. It has an age statement of 10 years.

A blend made mostly from rums aged 15, 17, and 21 years. However, the master blender felt that adding 10% of a particular pot-distilled 5-year rum made the rum much better. This rum can only be labeled as a 5-year rum under minimum age statement rules. The law is the law.

Ask yourself: If given the choice of a free bottle of one or the other, which would you pick? Would the small amount of 5-year rum in the second blend steer you to the safety of the first?

I know what I would choose.

These are the conundrums brands face if they choose to use age statements. Doing the right thing for a blend could prevent them from using an impressive age statement. Despite 90% of the rum being 15 years or older, consumers would still judge it as equal to other 5-year rums.

It’s likely not a coincidence that Mount Gay rums don’t use age statements. Likewise, a well-known Jamaican brand dropped age statements for some of their expressions, then brought them back later. Presumably, this was because their available stock wasn’t aged long enough to support the previous age statement.

These are the unintended effects that minimum age statements can cause. In the service of a quality-level metric that’s simple to understand and enforce (minimum age statements,) are they hindering blenders from making the best-tasting blend, regardless of minimum age? Yes, a brand doesn’t have to use age statements, but large numbers like 12, 15, and 21 resonate with consumers, so brands naturally like to use them.

An Alternative Calculation

Is there some happy medium where consumers can see numbers that are reasonably related to the age of the liquid while still preventing egregious misrepresentations?

The “obvious” solution to the question above is an average age statement. Cue the alarm bells again. “Heretic! Off with his head!” But let’s plunge on.

The simplest way to calculate an average age for a spirit is to add all the individual component ages and divide by the number of components. Thus, a blend of 2-year and 10-year aged rum would calculate as (2+10) / 2, i.e., 6 years. However, this calculation doesn’t consider how much of each component rum goes into the blend. Even if the blend were 99% 2-year and 1% 10-year, the average age would be 6 years. Clearly, this is not suitable.

To remedy this, we need to know how much of each rum is present. The mathematical term for taking into account how much of each component is weighted average.

As it turns out, three Caribbean basin countries allow the use of weighted average age statements: Guatemala, Costa Rica, and Panama. (See Note 1 at the bottom to learn more.) Knowing that weighted average age statements are used in significant rum-producing countries raises the urgency of understanding how they’re calculated.

How Does a Weighted Average Work?

Both the Costa Rican and Panamanian rum standards use the identical example to describe their weighted average age calculation. I’ve summarized that example in English below and followed it with additional commentary.

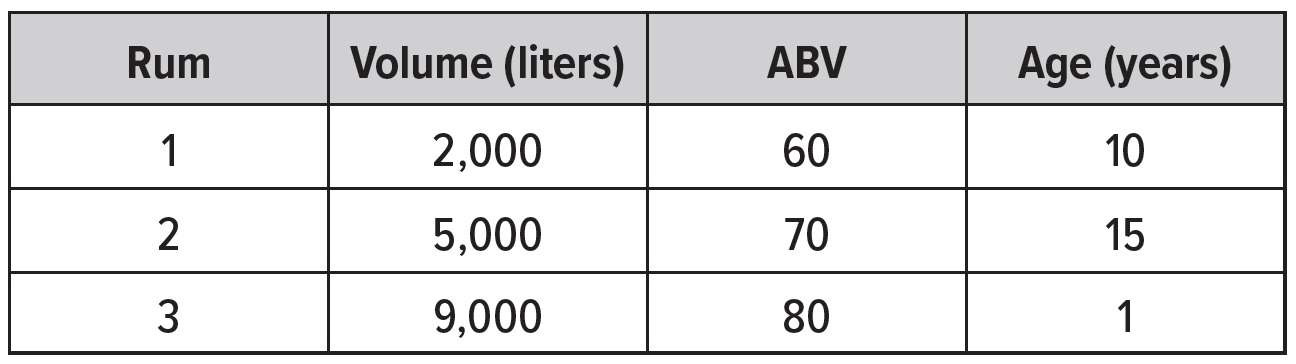

3.4 Weighted average age: A weighted average age can be used. The following is an example calculation:

Only the alcohol portion of each component is considered in the weighted average:

10-year rum: 2000 x 60% = 1,200 liters of alcohol

15-year rum: 5000 x 70% = 3,500 liters of alcohol

1-liter rum: 9000 x 80% = 7,200 liters of alcohol

Total volume of alcohol: (1,200 + 3,500 + 7,200) = 11,900 liters.

To calculate the weighted average, we need to calculate liter-years, i.e., one liter of alcohol aging for one year.

1,200 liters x 10 years = 12,000 liter-years

3,500 liters x 15 years = 52,500 liter-years

7,200 liters x 1 year = 7,200 liter-years

Adding all the liter-years together, we get 71,700 liter-years.

Finally, we divide the liter-years by the total liters: 71,700 / 11,900 = 6.02 years.

Thus, the above example rum blend could legally use a 6-year age statement in Panama, Costa Rica and Guatemala.

To those that would say, “How do we know the brand is truthful about the age of each component rum?” the same question could be asked of a brand using a minimum age statement. At the end of the day, we trust that excise officers and integrity will keep brands honest, but we won’t go down that rabbit hole here.

Why Use ABV?

Because the above calculation considers the component rum’s ABV, it might seem more complicated than necessary. If we ignore the alcoholic strength of each rum, the calculation is simpler: ((2,000 x 10) + (5,000 x 15) + (9,000 x 1)) / 16,000 liters = 6.5 years.

The difference between the two calculations (6.02 years vs. 6.5 years) is “close enough” in this example. But the simplified calculation enables a loophole that could be exploited to claim a significantly higher average age.

It’s unlikely that these three rums would be blended and sold at a resulting strength of 74% ABV. It’s much more likely that the blend will be diluted down to something like 40% ABV before bottling.

A devious blender might dilute the 15-year rum to 35% ABV before blending it with the others. The higher strength of the 1- and 10-year rums will bump the ABV up sufficiently.

Using the calculation where ABV isn’t considered, the average age increases by 2 years just by diluting the oldest rum in advance:

((2,000 x 10) + (10,000 x 15) + (9,000 x 1)) / 21,000 liters = 8.5 years.

By including the alcoholic strength of each component rum in the calculation, the weighted average age can’t be bumped up quite so easily.

Put another way: water doesn’t age, so don’t include it in the calculation.

Another Example

Let’s return to my earlier scenarios of 15-, 17-, and 21-year rums blended with 10 percent of a 5-year rum. What’s the weighted average of this blend?

For simplicity, assume we use 30 liters each of the 15, 17, and 21-year rums and 10 liters of the five-year rum. Also, each rum is 70% ABV. The calculation is then:

(30 x 0.7 x 15 years) + (30 x 0.7 + 17 years) + (30 x 0.7 x 21 years) + (10 x 0.7 x 5 years) / (100 x 0.7)

Doing all that math for you, the result is 15.9 years. I personally wouldn’t mind if this rum had an age statement of 15 years. Of course, I’d be more at ease if the component rums and their ages were provided.

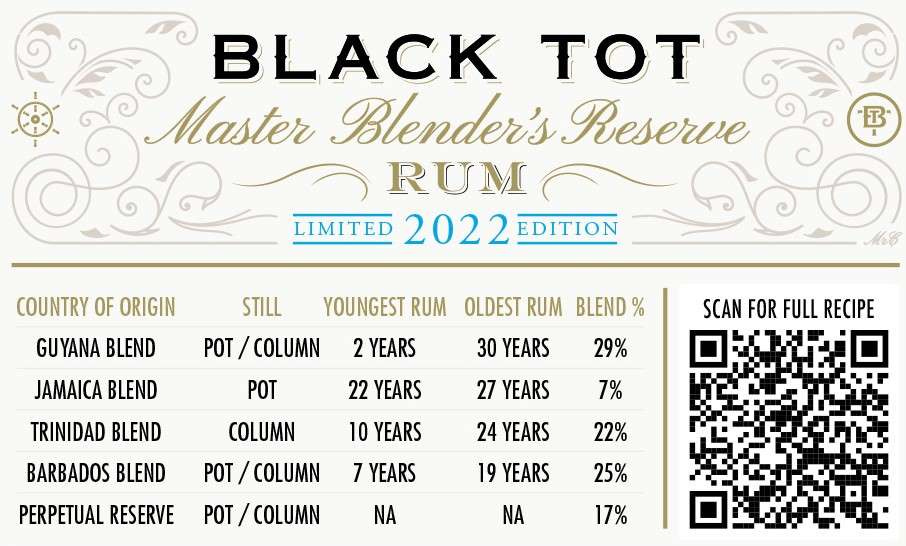

It’s worth noting that at least one brand has gone down this path: Black Tot Master Blender’s Reserve 2022.

The company’s website helpfully provides the source distillery, age and percentage of 18 component rums comprising 83% of the blend. The weighted average without considering ABV is 12.2 years, but under the minimum age rule, it would be just 2 years due to 6.7% of the blend being a 2-year DDL rum. The remaining 17% of the blend is dubbed a “Perpetual Blend” with no age given, but even if it was 1-year rum, the weighted average is still 10.3 years.

Summary

Wrapping things up, minimum age statements are the legal requirement in most countries, including the United States and the European Union. However, they may throw the baby out with the bath water in the service of simplicity.

Furthermore, minimum age statements aren’t a global standard. Even if you adamantly believe they should be, knowing how the alternate, weighted average age calculation works is valuable. With the current demands for transparency and disclosure from producers, an informed enthusiast might find it to be useful information, even if only available on a website rather than the label.

Note 1: For detailed examinations of the aging process and per-country rum regulations, see chapters 8 (“Rum Production: Aging”) and 17 (“Rum Regulations”) of Modern Caribbean Rum.

Very good solutions.

Great article, Matt! I like the idea of using weight average based on ABV. Clever. Obviously, the Black Tot approach is the ideal. From a marketing perspective, I think that creates more interest and intrigue than using any single age statement.