The Many Myths of Smith & Cross

It’s time to talk about Smith & Cross, an iconic Jamaican rum from the moment it arrived on the scene in 2009. Beloved by the craft cocktail community, Smith & Cross finds particular favor with tropical cocktail enthusiasts desiring a big dose of hogo in their libations.

For reasons not completely understood, this particular rum is a magnet for misinformation. A 19th-century aphorism states, “Falsehood Flies, and Truth Comes Limping After It.” A slightly newer take is, “A lie can travel around the world and back again while the truth is lacing up its boots.”

In a world where marketing hyperbole and misconceptions spread like wildfire via social media, it’s important to set the record straight with objective facts and credible sources. In what follows, you’ll discover the following about Smith & Cross:

It’s not navy strength as the Royal Navy defined it.

It’s not high ester within the context of the Jamaican rum universe.

It’s not made at Hampden Estate, although it may include some Hampden rum.

It’s blended in Amsterdam by E&A Scheer.

It’s composed of rums from several Jamaican distilleries.

It’s very unlikely to be a blend of solely Plummer- and Wedderburn-style rums.

Before jumping in, let me say that I wholeheartedly enjoy Smith & Cross. It was my gateway into Jamaican rum, and it’s been a staple in my bar for over a decade.

Origin Story

Some of the misconceptions about Smith & Cross originated from its first product page, published in 2010 by Haus Alpenz, the rum’s US importer. While this original product page is no longer on the web, it lives on via the Internet Wayback Machine (Link). Rather than reproducing the entire page’s contents here, I’ll quote the relevant excerpts later on as we address them.

If we ask ChatGPT-4, the ultimate arbiter of “conventional wisdom” on the internet, about Smith & Cross, it authoritatively states:

“This Jamaican 100% pot still, high ester rum is one of the heaviest pot still rums available and is said to be reminiscent of 19th century Jamaican rum. Smith & Cross is made using molasses, cane juice and syrup from sugar at the Hampden Estate mill, and is distilled at the estate’s own distillery.”

We can’t blame ChatGPT for getting the story wrong. It only “knows” what it finds on the internet. In the 14 years since Smith & Cross launched, hundreds of high-profile publications, rum reviewers, and online liquor stores have spread the myths and misconceptions to all corners of the globe.

I won’t name and shame anybody other than the author of these stories:

Yes, yours truly is guilty spreading misinformation about this rum. While I can’t change the past, I can provide a more accurate rendition of the Smith & Cross story for future writers covering this rum.

Myth: Smith & Cross is Navy Strength

Reality: It’s “proof strength,“ which is not the same as “navy strength.”

(For American readers, ignore what you know about proof, i.e., that a spirit’s proof is twice its ABV. Our frame of reference here is the British Imperial proof system, which predates America’s proof system and is more complicated.)

In the British imperial system, proof strength corresponds to 57% ABV. From the early 1800s onward, the Royal Navy issued its rum at around 54.5% ABV. Yes, Royal Navy rum was underproof. While 54.5% and 57% ABV aren’t dramatically different, the Royal Navy and British excise officers certainly didn’t consider them equivalent.

If you don’t wish to take my word for the above, consider the Black Tot Last Consignment rum, which is actual Royal Navy rum that has been bottled, undiluted. It’s alcoholic strength? 54.3% ABV. (The small difference between 54.3% and 54.5% is small enough to be negligible.)

Simply put, the Smith & Cross label is not historically accurate in this regard.

For a deeper dive that dismantles the myth that 57% ABV is navy strength, see the article, Navy Rum Strength isn’t 57%. To learn more about the British imperial proof system, see Understanding British Imperial Proof Strength.

Myth: Smith & Cross is High Ester Rum

Reality: While Smith & Cross has more esters than many rums not made in Jamaica, Smith & Cross is on the lower end of the scale, ester-wise, relative to traditional Jamaican rum.

Long ago, Jamaican rums were divided into four categories:

Common Clean (80-150 gr/hlAA)

Plummer (150-200 gr/hlAA)

Wedderburn (200-300 gr/hlAA)

Continental (700-1600 gr/hLAA)

Those terms aren’t particularly important in the rum trade these days, but they live on partly because they sound cool in marketing copy.

I have seen a Gas Chromatography (GC) analysis of Smith & Cross rum, performed in 2018 in a certified laboratory, and the total esters were 147 gr/hlAA. Using the historical categorization above, Smith & Cross falls into the upper end of the lowest category, i.e., Common Clean.

When enthusiasts and blenders refer to high ester rums, they typically mean rum in the “Continental” style between 700 and 1600 gr/hlAA. Examples of Jamaican marks in the Continental style include:

I’m not suggesting that Smith & Cross isn’t highly flavorful. Rather, the issue is the common misperception that highly flavorful and “high ester” are synonymous. Esters are but one component in a collection of different classes of flavor molecules collectively known as volatile compounds. Other volatile compounds include higher alcohols such as propanol and isopentanol. Informally, higher alcohols are known as fusel oils.

By looking at a spirit’s volatile compounds rather than just its esters, we can better understand its flavor intensity. In the same Smith & Cross GC analysis, the volatile compounds were 635 gr/hlAA. That value is several times higher than your typical Spanish heritage rum but middle-of-the-road for a Jamaican rum.

It’s also important to understand that Smith & Cross’s relatively high strength (57% ABV) heightens the perceived flavor intensity. If you diluted it to 43% ABV, a typical rum strength, its aroma and flavor wouldn’t seem so intense.

As a point of reference, Plantation’s Xaymaca has esters of 156 gr/hlAA and 312 gr/hlAA of volatile compounds. Compared to Smith and Cross, Xaymaca has roughly the same ester level but less than half the volatile compounds. Put another way, higher alcohols play more of a role in Smith & Cross’ flavor profile than they do with Xaymaca.

Before moving along, I must stress that rum blends change over time, and the lab data cited above represents a particular moment in time. However, unless Smith & Cross’s blend changed significantly over the years, it’s not high ester within the realm of Jamaican rum.

For those interested in a deeper look at esters and volatile compounds, see Esters, Volatile Compounds, and Congeners - What’s the Difference?

Myth: Smith & Cross is made by Hampden Estate

Reality: Smith & Cross contains rums from several Jamaican distilleries and is blended by E&A Scheer in Amsterdam.

If you dig into the recent history of Hampden Estate and the Smith & Cross brand, the likelihood that the rum was wholly distilled by, much less bottled at Hampden Estate, is extremely low. Among the reasons why Hampden Estate isn’t the source of Smith & Cross, consider the following:

Smith & Cross came to market in 2009.

The Hussey family purchased Hampden Estate in 2009 and started aging rum at Hampden for the first time in the Estate’s history.

The original 2010 product page for Smith & Cross (above) notes that both component rums (more on them later) are aged, with one aged up to three years.

Simply put, Hampden Estate couldn’t have made Smith & Cross in 2009, as it didn’t have aged rum to work with.

While this could be considered only circumstantial evidence, there’s stronger evidence to consider. People with direct knowledge of the Smith & Cross blend have stated that it contains rums from several Jamaican distilleries, which E&A Scheer blends.

Could some of the blend come from Hampden? Sure! A longstanding blending technique is to create a base of lighter rums, then add a smaller amount of pungent, high-congener rums as a “top note.” Hampden specializes in making this type of rum.

Where did this myth originate? The earliest citation of this misinformation that I’ve found is a 2013 Chemistry of the Cocktail post stating: “The current iteration of Smith & Cross rum is produced by the Jamaican distiller Hampden Estate.”

Myth: Smith & Cross is a blend of Plummer and Wedderburn Rum

Reality: Smith & Cross’ ester level is less than the requirements for both Plummer- and Wedderburn-style rum.

Returning to the 2010 Haus Alpenz product page, it notes:

“Here we offer a blend of approximately equal parts Wedderburn and Plummer, the former aged for less than a year, and the latter split between 18 months and 3 years on white oak.”

As we saw earlier, the minimum ester level for a Plummer-style rum is 150 gr/hlAA, while 200 gr/hlAA is the minimum for Wedderburn-style. Imagine we had two rums with exactly those ester levels, and we blended them 50-50. The result would contain 175 gr/hlAA of esters.

But wait, there’s more! The category that a Jamaican rum falls into is determined by its ester levels after distillation and before aging. In general, aging increases a rum’s ester level, making it even less likely that a blend of lightly aged Plummer and Wedderburn rums would have an ester level of only 147 gr/hlAA.

About The Smith & Cross Name

Having debunked a few myths, let’s now turn to the Smith & Cross name. The previously mentioned product page says:

The mark of Smith & Cross traces its lineage to one of England’s oldest producers of sugar and spirits. It’s history dates back to 1788, with a sugar refinery located at No. 203 Thames Street by the London Docks. Over time, the firm and its partners became prominent handlers of Jamaica rum, with extensive cellars along the river Thames. Smith & Cross today stands as successors in trade to Smith & Tyers and White Cross, both having previously operated side by side for generations in the house of what is today Hayman Distillers.

Having spent countless hours burrowing into the early London rum trade, I set out to see what I could corroborate from the above paragraph.

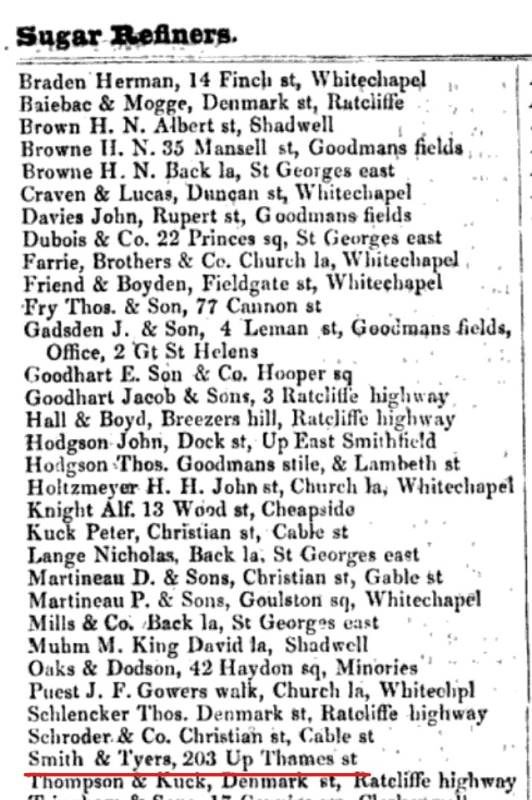

Information about Smith & Tyers is relatively easy to find via archival sources. The company dates to 1840 and as the Haus Alpenz history states, operated for a few years at 203 Upper Thames Street. Per an 1854 newspaper notice, Smith & Tyers was a manufacturer of cordial flavors, shrub acid, and spirit coloring. In the 20th century, the company was listed as a spirit rectifier.

As for “Smith & Cross” and “White Cross,” I could not find any evidence of a London-based company with those names in the 1700s or 1800s. I also could not find any connection between Smith & Tyers and the year 1788. The footnote section below further details the history of Smith & Tyers and its connection to Hayman Distillers.

Conclusion

Some people might dismiss my quest for objective truth regarding this rum, claiming there’s little harm in a bit of creative hyperbole. I disagree.

We must constantly strive to know the truth. If we don’t, the truth won’t be available when it matters most.

Or, as Lance at The Lone Caner wrote in his comments on a draft of this story, “The real danger is not that fake nonsense is out there, but that too many people will believe it.”

Again, Smith & Cross is an excellent rum that I regularly recommend to others. But it’s time to put aside the mythology and misconceptions and recognize Smith & Cross for what it is. No embellishment is necessary.

Footnotes

The 1793 Wakefield’s Merchant and Tradesman’s General Directory for London shows “Shaw and Church, sugar coopers” rather than “Smith & Cross” at 203 Upper Thames Street.

If Smith & Cross were a prominent handler of Jamaican rum at the turn of the 19th century, it should appear regularly in newspapers, business archives, and parliamentary reports, but it doesn’t. Here’s one such example, a listing of significant London rum importers between 1797 and 1801. Smith & Cross is not in the list. Notably, both Plummer and Wedderburn appear on this importers list as well as the Smith & Cross label.

A website about the history of London’s sugar refiners contains a substantial amount of history for Smith & Tyers, including:

Charles Smith was born in 1806 to John & Margaret Smith.

Robert John Tyers was born in 1802 to John & Elizabeth Tyers.

“In 1840 Charles went into partnership with Robert Tyers under the name of Smith & Tyers Liquid Sugar Refiners, though they continued their other lines of business. Tyers appears in 1841 to also have had a fish sauce warehouse at 58 Borough High St. By 1853 Smith & Tyers, sugar refiners, colour manufacturers & vinegar and pickle makers, had moved from Upper Thames St … to 14 Green St, Wellington St, Blackfriars Rd, Southwark…”

After Charles Smith died, his son Frederick took over: “…in 1881 he [Frederick] was a compounder and sugar refiner employing 11 men, and in the new century he was a (licensed) rectifier and compounder, emphasising the mixing of spirits rather than sugar refining even though the trade directories of both 1895 and 1915 listed Smith & Tyers under Sugar Refiners.”

Frederick Smith died in 1923.

The above information is corroborated from other sources, including a business directory and newspaper ads of the era:

The 1920 Harpers Directory notes Smith & Tyers as compounders of British cordials:

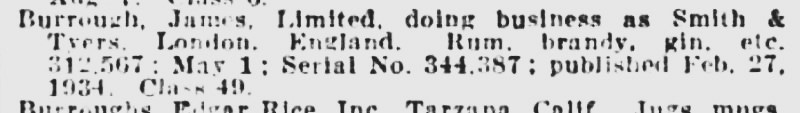

In 1934, the British company James Burrough Ltd trademarked Smith & Tyers in the US shortly after prohibition ended. Burrough is best known as the creator of Beefeater gin.

Through a complex set of events in the 1980s, the “James Burrough Limited Fine Alcohols Division” was reincarnated as Hayman Distillers, which today is part of Hayman Limited. The company owns the Hayman’s Gin, Smith & Cross, and Merser Rum brands.

Substack Discovery is getting pretty good for me to find this by chance. Makes my rum “scholarship” look absolutely bush league. Thank you for your service.

Hi Matt;

Excellent article on the Smith & Cross So glad you cleared up the misconceptions on this rum but like you I still enjoy it.My favourite rums only see a drop of water or sometimes in an old-fashioned cocktail.Every now and then when sharing my rums with cola loving friends I partake of a Smith & Cross cola cocktail.

As a Naval Reservist serving on Canadian ships in the mid sixties I did enjoy the " tots"-overproof for sure!

Take care

Stan