Dunder, Muck, and Acid - Demystifying Jamaica Rum's Secret Sauce

Jamaica rum’s hallmark is its bold, funky, and fruity flavors, which are rarely seen in rums from other locales. People new to rum sometimes ask, “What is funk?” A typical reply is, “When you’ve tasted it, you’ll know.”

Jamaica rum’s bold flavors derive from fermentation components that, while not unique to Jamaica, are emblematic of the island’s rum-making. Unfortunately, what these components are and how they work often confuses enthusiasts and writers.

Dunder is the best known of these components, acid and muck much less so. To help enable a more accurate understanding of their contributions to Jamaica’s unique rum, I’ve summarized key details about each of them below, along with a quick-reference infographic.

Fermentation Forward

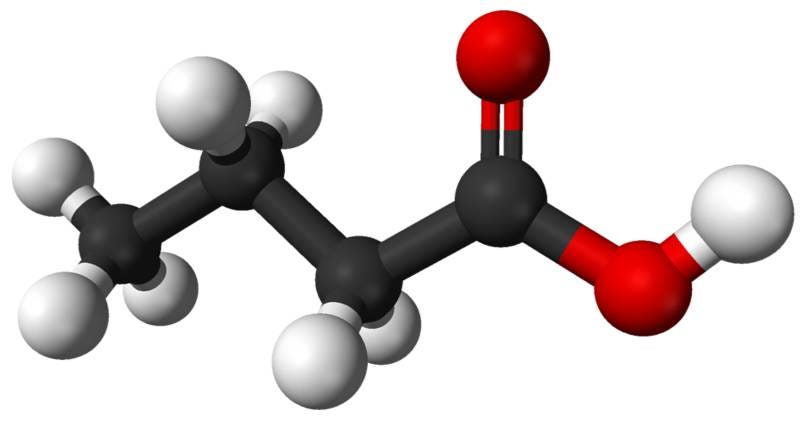

Unlike most rum sold today which is aging forward, Jamaica’s rum is fermentation forward. I discussed this concept in an earlier article, Rum, Ratios, and Flavor. Fermentation forward simply means that most of the rum’s flavor was created during fermentation. When yeast consumes the sugar and other components in the mash during fermentation, it emits many types of organic molecules, including organic acids, alcohols, and esters.

Some of these compounds, including methanol, are poisonous and/or unpleasant tasting and are mostly removed by the distillation process. What remains in the newly distilled rum is mostly ethanol, along with lesser amounts of organic acids, higher alcohols, and esters. These non-water, non-ethanol compounds are collectively called congeners, and they give rum its flavor. Of course, if you subsequently age the rum, it will acquire additional flavors, but those flavors will be different than the fermentation-created flavors.

At best, a rum mash of molasses, water, and a typical yeast (Saccharomyces Cerevisiae) will create a modest amount of flavor compounds. To supercharge fermentation-created flavor, you need to play the game differently. That means using a different class of yeast and providing an environment optimized for emitting large amounts of desirable congeners.

Without going deep into fermentation chemistry, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe species of yeast is colloquially known as “wild yeast,” meaning they naturally occur in the air, water and soil. Different yeast strains create different rum, and each Jamaican distillery has its own ambient pombe strains. Pombe yeast works best in a more acidic environment than what’s optimal for the Saccharomyces Cerevisiae species used in other locales. This is no small detail. As you’ll see below, different types of organic acid molecules play a pivotal role in Jamaica’s unique rum-making process.

Dunder

Dunder is a Caribbean name for the slightly acidic liquid that remains in a pot still after distillation. Elsewhere, it’s also known as stillage, vinasse or lees. Once drained from the still, the dunder cools and rests for many days. During the resting interval, dead yeast cells and other solids sink to the bottom of the tank and form a sludge.

When combining and mixing the ingredients for a new batch of rum mash, liquid dunder can replace most of the water that a conventional fermentation would require. After fermentation starts, the dunder-contributed acid molecules combine with yeast-created alcohol molecules to create esters. Simply put, dunder creates a better environment for ester formation than regular water.

Of note for anyone who thinks that dunder is particularly exotic, the sour mash whiskey process uses the same technique to enhance flavor creation.

Regarding dunder’s etymology, a 1794 book notes, “From redundar, Spanish -- the same as redundans in Latin.” (In English, redundar/redundans means overflow.)

There’s some misguided folklore about “dunder pits,” wherein Jamaican distillers supposedly store dunder and occasionally toss in a goat head, dead bats, and something equally horrible. It’s not true. However, there are muck pits, which we’ll look into shortly.

Distilleries Using Dunder: Hampden, Long Pond, Clarendon, New Yarmouth.

(Cane) Acid

Acid, as used in Jamaica rum making, is essentially a crude vinegar made from cane juice. Like dunder, acid can comprise a significant percentage of a rum mash. Fun fact: many household vinegars also derive from sugarcane, but is far more pristine and sterile than the acid Jamaica’s distilleries make. As with dunder, the additional organic acid molecules in the mash boosts ester production.

How is acid made? In 1905, Charles Allan, Jamaica’s fermentation chemist, wrote:

Acid is made by fermenting rum cane juice which has been warmed in the coppers. To this juice is added dunder and sometimes a little skimmings. When fermentation is about over the fermented liquor is pumped on to cane trash in cisterns and here it gets sour. Into these cisterns sludge settling from the fermented wash is from time to time put. This acid when considered fit for use smells like sour beer.

Editorial note: coppers are the large metal pans used to boil and reduce sugar cane juice to crystalize it. Skimmings are the crust that forms on top of boiling cane juice.

Besides supplying acidity to the fermentation, the acid also contains wild yeast and bacteria that previously resided on the cane stalks, thus ensuring the fermentation uses endemic yeast from the cane fields.

To briefly recap before continuing, dunder and acid are both optional components in a rum mash. Both enhance the conditions for wild yeast to create flavorful congeners.

Distilleries Using Acid: Hampden, Long Pond, Clarendon, Worthy Park, New Yarmouth.

Muck

If wild yeast fermentation is the hero of Jamaica rum’s story, then muck is the anti-hero twin — at least in the early stages. While fermentation consumes sugar to emit alcohol and flavorful congeners, muck is a parallel process wherein bacteria putrefies the sludge that previously resided at the bottom of the fermentation and dunder settling tanks.

The sludge contains dead yeast cells and other organic matter that the bacteria consumes and converts into longer-chain organic acids, such as butyric and isobutyric acid. The aroma of such acids is described as vomit, rancid butter, and rotten cheese. Having peered down into a muck pit, I can confirm that the smell is easily among the most horrifying things I’ve ever experienced.

Why would anyone make vile-smelling muck? The short answer is that these more complex acid molecules aren’t normally present in a normal fermentation. While they smell disgusting on their own, when they combine with alcohol molecules, the result is complex esters like ethyl butyrate and propyl hexanoate. These two esters smell of pineapple and blackberry, respectively.

The full muck-making process is too complex to describe here. What’s important is that the muck eventually combines with other organic materials to create flavour. Unlike dunder or acid, the flavour doesn’t enter the story until after several weeks of fermentation. If the muck/flavour is added too early, the bacteria would negatively impact the fermentation. However, once regular fermentation is over, adding flavor injects a fresh bath of complex acid molecules that combine with alcohol molecules to make more exotic esters.

Related to, but distinct from muck pits, are muck graves, which are holes in the soil near the distillery. The bacteria strains in a muck pit are also present in the distillery’s soil. However, by filling these holes with fermenter bottom sludge, the bacteria replicate faster as the dead yeast cells in the sludge act as a food source for the bacteria. After several years, the grave’s contents are dug up and added to the muck pit to rejuvenate the muck pit’s bacterial population.

Muck is only used to make the highest ester marks, such as Hampden’s DOK, Long Pond’s TECC, and New Yarmouth’s NYE/WK. (For more information on the marks made by Jamaica’s distilleries, see my page, Jamaican Rum Marques Roundup.

Distilleries Using Muck: Hampden, Long Pond, New Yarmouth.

Summary

The above barely scratches the surface of how dunder, acid, and muck are created and used. To briefly recap, dunder, acid, and muck are fermentation components that enhance the creation of flavor compounds in a rum wash. Dunder is used in several locales outside Jamaica, notably certain Haitian clairins and Grand Arôme rums from Martinique and Reunion. But acid and muck are exclusive to Jamaica for the most part.

Dunder and acid are components of the initial rum mash before fermentation starts. Muck and flavour don’t enter the picture until after fermentation but before distillation. Of the three, muck is the most secretive, and each distillery treats its muck process as a trade secret.

The infographic below summarizes the key points from above.

As always, the infographics are super helpful. Now I want to try a sour mash whiskey and see what similar vibes it has to Jamaican rums.

You mention Grand Arome from Guadeloupe uses Dunder. Shouldn’t that be Martinique?